Practice of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in IBD

Vol. 29, Issue 1 (March 2024)

|

Karoline Soares Garcia, MD

Department of Gastroenterology, University of São Paulo School of Medicine

São Paulo, Brazil

|

|

|

Camilla de Almeida Martins, MD, PhD

Department of Gastroenterology, University of São Paulo School of Medicine

São Paulo, Brazil

|

|

|

Natália Sousa Freitas Queiroz, MD, PhD

Health Sciences Graduate Program, School of Medicine, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR)

IBD Unit, Hospital Santa Cruz

Curitiba, Brazil

|

Rationale

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) has emerged as a promising strategy for optimizing the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). It is currently recognized as part of the available tools to assess response to therapy and ensure maintenance of remission in IBD. The reasons to routinely perform TDM testing rely on three main factors: the observation of loss of response to biologics, which, especially for anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents, is strongly associated with pharmacokinetic failure and immunogenicity; the association between drug exposure and response and the variability in drug clearance explained by pharmacokinetic covariates.1, 2

Anti-TNF drugs are effective treatments for the management of IBD but treatment failure is common. In a recently published prospective observational study of 1610 biologic-naïve Crohn’s disease (CD) patients treated with infliximab or adalimumab (PANTS study), week 14 primary non-response was observed in 23.8% of patients and the rate of week 54 remission was 36.9%. The study also demonstrated that treatment failure is predicted by low drug concentrations and mediated in part by immunogenicity. It was found that 7 and 12 mg/L week 14 concentrations for infliximab and adalimumab, respectively, were associated with both remissions at week 14 and 54.3

The relationship between higher biologic drug concentrations and favorable outcomes (including clinical remission, endoscopic healing, or resolution of fistula discharge) has been demonstrated for all biologics in post hoc analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and retrospective studies.4 This association is well established for anti-TNF agents, especially infliximab (IFX).4

Exposure-response relationships are also evident for vedolizumab (VDZ) and ustekinumab (UST). The GEMINI I/II trials observed that ulcerative colitis (UC) and CD patients with the highest quartile of serum vedolizumab levels had a greater likelihood of clinical remission.5, 6 For UST, studies support the association between ustekinumab levels and positive outcomes during the induction and maintenance phases in CD patients.7, 8

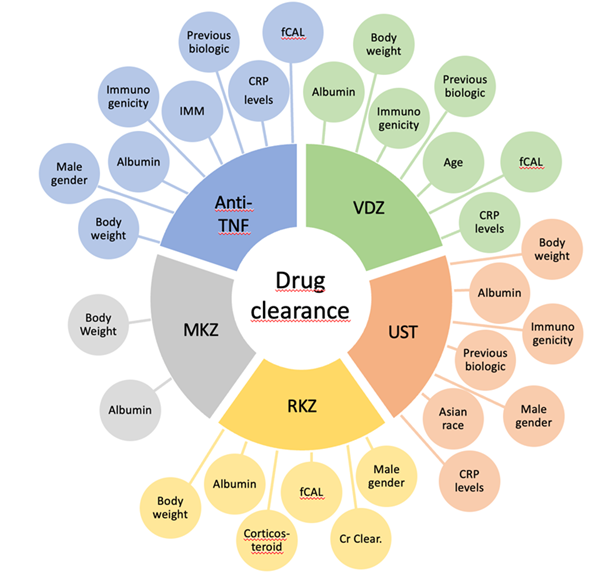

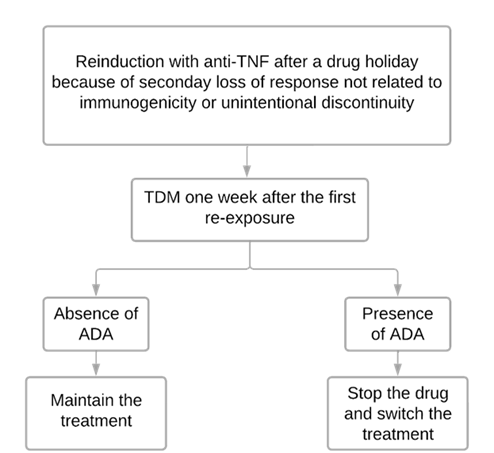

Several studies have demonstrated an association between higher drug clearance, suboptimal biologic concentrations, and undesired therapeutic outcomes.9 The mechanisms related to the clearance of biologic drugs are fecal loss of protein, linking to anti-drug antibodies, intracellular catabolism, and intensification in target load.9, 10 Numerous factors are related to drug clearance. In particular, body weight, serum albumin, and the formation of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) have been associated with low drug levels of almost all biologics.9 Figure 1 summarizes the variables associated with drug clearance of all biologics available.

Various factors, such as body weight, male gender, serum albumin, immunogenicity, prior biologic therapy, inflammatory burden, and the use of concomitant immunomodulators influence drug clearance for anti-TNF in IBD.11-16 The route of administration also affects pharmacokinetic behavior. The bioavailability of immunobiologics administered subcutaneously is extremely variable among patients, ranging from 50 to 80%.10, 17 Recently, a RCT showed noninferiority of IFX subcutaneous to IFX intravenous concerning pharmacokinetics, with efficacy and safety similar between both groups.18

Figure 1

For vedolizumab, factors affecting drug clearance include body weight, albumin, immunogenicity, previous biologic therapy, age, higher endoscopic Mayo score, fecal calprotectin, and C-reactive protein (CRP).9, 19 A study by Rosario et al. observed that there is no difference of serum vedolizumab concentrations between intravenous and subcutaneous administration.19 For ustekinumab, drug clearance is influenced by factors such as body weight, serum albumin, immunogenicity, previous use of biologics, male gender, Asian race and higher CRP levels.20, 22

Whilst data for the new biologic drugs risankizumab and mirikizumab is limited, Suleiman et al. observed that body weight, albumin, fecal calprotectin, corticosteroid use, creatinine clearance and male gender were related with the risankizumab clearance.23 Also, recent findings by Chua et al. associated serum albumin and body weight with mirikizumab clearance.24

How to perform TDM: Reactive x Proactive TDM

Reactive TDM

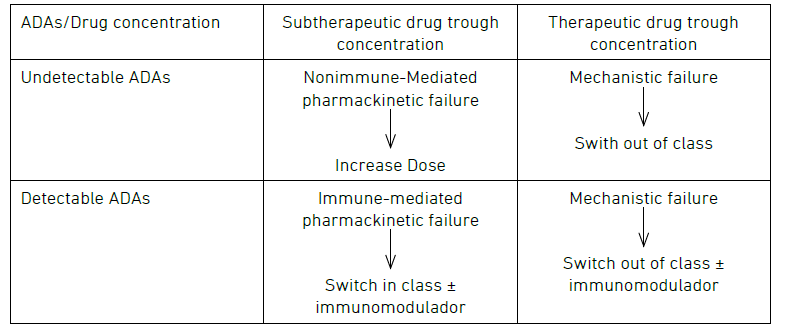

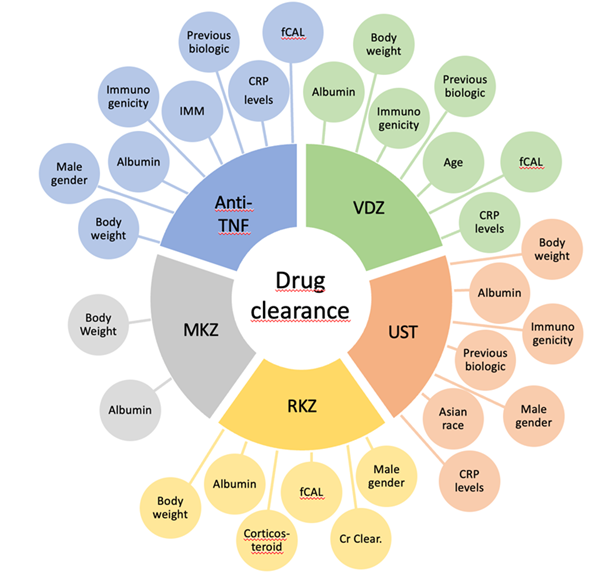

Reactive TDM includes the measurement of serum drug and anti-drug antibody concentrations to guide treatment changes. It is performed when patients experience a disease flare and helps to elucidate the mechanism of primary or secondary loss-of-response to biologic therapy.2, 10, 25 Reactive TDM is proven to be more cost-effective than empiric dose escalation.26, 27 It is also endorsed by various gastroenterology societies, medical associations, and expert groups.2, 28-33 The algorithm proposed is described in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Algorithm for reactive TDM.

Some interesting questions have arisen about this algorithm. First, in the context of an immune-mediated pharmacokinetic failure, is switching in class a feasible option? A large retrospective study by Vande Casteele et al. indicates a greater chance of developing ADAs to a second anti-TNF in patients who used anti-TNF previously and developed ADAs or had subtherapeutic drug levels.34 Interestingly, Costable et al. observed that previous immunogenicity to anti-TNF is not related to an increased risk of immunogenicity of vedolizumab or Ustekinumab.35

This initial issue leads to a second question: which levels of ADAs should be considered relevant, and which ones can be addressed through dose escalation? Two studies suggest that higher ADA levels are related to undetectable drug concentrations and cannot be overcome with dose escalation.36, 37 Additionally, a drug-tolerant assay with detectable drug concentration and the presence of ADAs seems clinically irrelevant.37 Conversely, overcoming low-titer ADAs is possible through dose escalation, reducing dose interval and/or adding an immunomodulator.38, 39 Nonetheless, distinguishing between low and high ADA titers remains challenging due to assay-specific nuances, with scarce data available for assays beyond Homogenous Mobility Shift Assay (HMSA) and biologics other than IFX.40, 41

Recently, an expert consensus by Cheifetz et al. recommended using HMSA for antibody measurement. It considered low titer antibodies to infliximab < 10U/mL for the HMSA.32 According to this consensus, stopping treatment with infliximab or adalimumab is not recommended until the drug concentration reaches a minimum of 10–15 µg/mL.32

Proactive TDM

A proactive TDM approach is defined by measuring drug and antidrug antibody levels, regardless of disease activity, targeting optimal levels for achieving better outcomes and preventing failure of therapy. It is important to emphasize that optimal serum drug levels vary according to the drug, disease phenotype, treatment target, and phase of treatment (induction or maintenance).4, 32

Numerous data exploring the exposure-outcome relationship have been published for anti-TNF agents, and there is increasing evidence for TDM with vedolizumab and ustekinumab either. However, we must point out that TDM for these new biological drugs is less consistent in the literature and less available than for anti-TNF agents, limiting its use in most patients.4, 32 TDM data for rizankizumab and mirikizumab are still limited, given the most recent use of these medications, and until now there is no guideline endorsing TDM for these drugs.

Although proactive TDM is still less established than reactive TDM, the proactive approach for anti-TNF agents is recommended by several medical societies and expert groups.32, 42, 43 This strategy is probably most important in patients with high inflammatory burden (e.g. during induction therapy, in those with more severe and extensive disease, and pediatric patients), and increased drug clearance, whose risk of inadequate drug exposure, immunogenicity, and treatment failure is high. This subgroup of IBD patients is likely to benefit more from proactive TDM and enhanced early biological efficacy.4, 32

When to perform TDM?

Induction and pos induction

Higher biological drug levels during and straight after the induction phase have been associated with better short- and long-term outcomes in IBD, including better rates of response to therapy and patients' quality of life, pharmacoeconomic benefits, and prevention of future complications.44, 46 On the other hand, inadequate drug exposure has been associated with immunogenicity and loss of response to the drug.47, 48

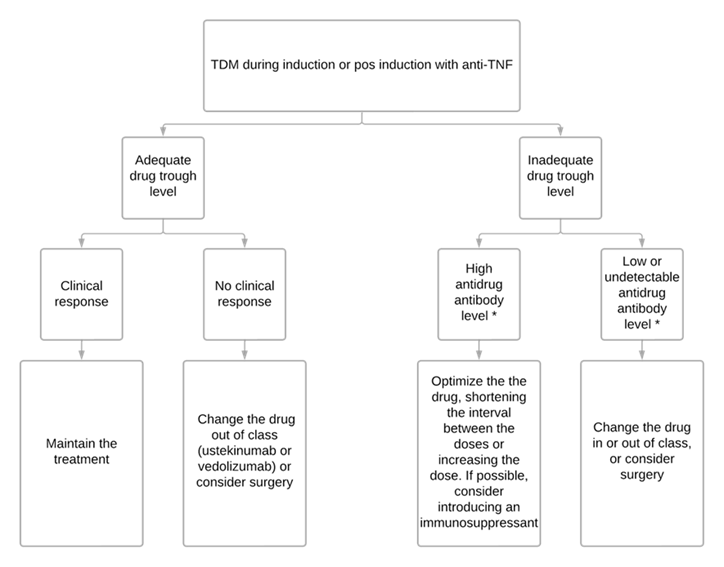

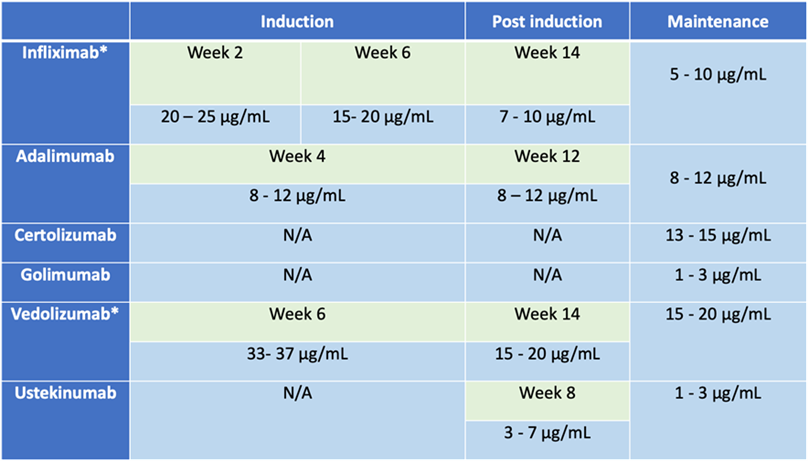

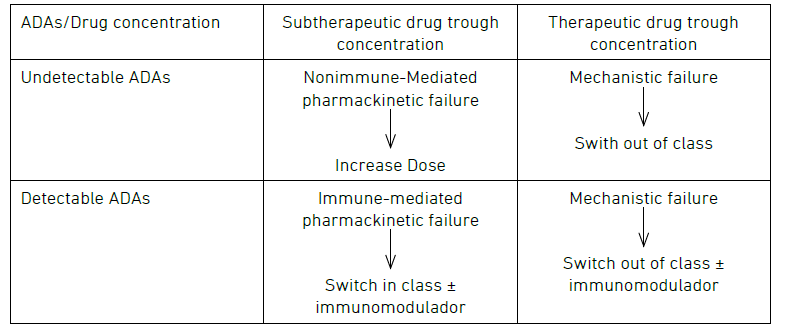

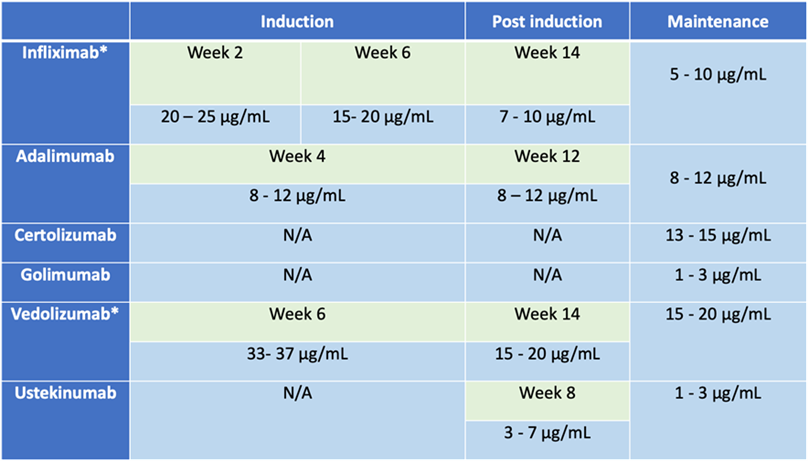

Early proactive TDM offers two main applications: monitoring patients to ensure adequate drug exposure (table 1), and optimizing infliximab monotherapy as an alternative to combination therapy with an immunosuppressant (ISS) in selected patients.32 Avoiding immunosuppressants has been considered in patients at high risk of infections and malignancies since studies have shown that optimized infliximab monotherapy guided by proactive TDM optimization has similar efficacy to combination therapy with thiopurines.49 Figure 3 summarizes the suggested approach.

Figure 3

Table 1

Maintenance

Numerous studies assessing the exposure-outcome relationship for biological drugs have shown that higher anti-TNF drug levels during maintenance are associated with more favorable therapeutic outcomes, such as lower rates of relapses, less need for hospitalizations and surgeries, and higher rates of corticosteroid-free remission, endoscopic healing and fistula closure.50-55 The NOR-DRUM B trial demonstrated that in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including UC and CD, proactive TDM during maintenance therapy with IFX was more likely to lead to sustained disease control compared with clinically based treatment.56

As recommended by Cheifetz et al. we usually try to monitor patients under anti-TNF therapy TDM once a year, but some barriers, such as the cost of the tests, can make this systematic approach difficult.32

Guiding treatment de-escalation

Despite the current discussion regarding cycling biological therapy in IBD patients in sustained deep remission, the risk of relapse after anti-TNF discontinuation in CD patients is approximately 40% at one year, and 50% at two years.57, 58 With that in consideration, we do not routinely withdraw biological agents from patients in remission. We agree that discontinuing biological therapy should only be considered in special situations and after careful assessment of risks and benefits.

Proactive TDM may be used to decrease virtual supra-therapeutic exposure to a drug in patients in remission.32 Lucidarme et al. evaluated IBD patients in clinical and biological remission, and they found that TDM‐guided de-escalation when infliximab trough level (ITL) is > 7mg/L was associated with a decreased risk of relapse compared with clinically guided de-escalation.59 Additionally, Petitcollin et al. studied factors that influence relapse after IFX de-escalation in IBD patients in deep remission.60 The authors showed that ITL < 2.4 mg/L after de-escalation was an independent predictor of relapse.60 Following the pointed studies and the latest TDM consensus, we consider de-escalating the dose of a biological agent in patients in deep remission when the drug trough level is above the minimum value considered appropriate (table 1). Also, we check whether the trough level remains adequate after this procedure.

Another utility for proactive TDM is when considering discontinuation of the immunossupressant in patients on combotherapy. Drobne et al. evaluated CD patients under anti-TNF in combotherapy and showed that ITL > 5mg/mL at the time of ISS withdrawal was predictive of not losing response to infliximab.61

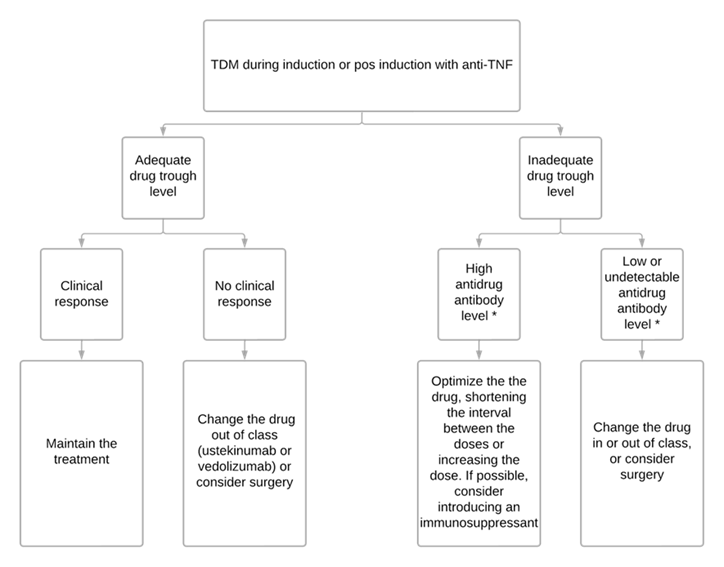

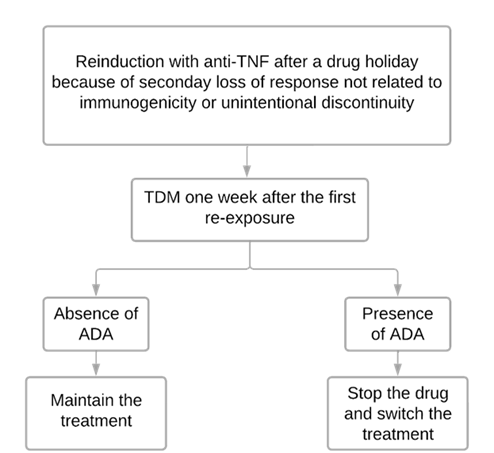

After a drug holiday

A drug holiday is defined as a delay of three or more doses of a biological agent.62 Re-exposure to anti-TNF after that time poses a greater risk of immunogenicity and, therefore, a higher risk of therapy failure and infusion reactions.63-67 The use of immunosuppressant in combination with anti-TNF after a drug holiday has been associated with a decrease in both risks (infusion reactions and pharmacokinetic failure).63-67 Even though it is used in some centers, premedication with corticosteroids or antihistamines has not been found to be effective in preventing infusion reactions.68, 69

An important strategy to prevent reported complications is guiding anti-TNF reintroduction by TDM.32, 70, 71 As the greatest risk of a serious infusion reaction occurs early (before the second or third infusion after a re-exposure) we usually restart anti-TNF therapy in association with immunosuppressant and collect samples for TDM one week after the first reinduction dose (Figure 4).32, 70, 71 However, in centers where a point-of-care test is available, the test can be done just before the second infusion.32 The second dose is recommended only after it has been confirmed that there are no high levels of antidrug antibodies.32, 70, 71 We should not restart the drug if it was previously discontinued due to the development of antidrug antibodies.32 There is not much research on the reintroduction of VDZ and UST after a drug holiday, but it’s known these drugs are relatively low immunogenic and TDM for them isn’t easily available, so we could restart them without TDM.32

Figure 4

Special situations

Perianal Crohn’s disease

Given the greater inflammatory burden and the need for higher anti-TNF concentrations to achieve more stringent outcomes, such as early fistula response and fistula healing, patients with perianal Crohn’s disease (pCD) are more likely to be exposed to subtherapeutic anti-TNF levels.44, 72 ITL predictive of fistula response at week 14 were ≥ 20.2 mg/ml at week two, ≥ 15 mg/ml at week six, and ≥ 7.2 mg/ml at week 14.44, 72 Considering these points and the limited options for treating this phenotype of IBD, monitoring drug and antidrug antibody levels, and not giving up treatment until optimizing therapy is of the utmost importance(44,72). As suggested by Papamichail and Cheifetz, we usually optimize IFX in pCD until an ITL of at least 10-15 μg/ml is achieved.41

Perioperative care

It seems that prior biologic exposure and detectable serum drug levels (anti-TNF, vedolizumab or ustekinumab) are not significantly associated with a high risk of infections or surgical site complications in the postoperative period.73 A large prospective multicenter trial assessing the risk of surgery and biologics (The Postoperative Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease—PUCCINI) evaluated 947 patients (382 with exposure to anti-TNF up to 12 weeks before surgery), and the rates of overall infectious complications or surgical site infections did not differ between patients with previous exposure to anti-TNFs and controls.73 Despite controversies surrounding this topic, we do not believe TDM has a great impact on guiding key decisions in perioperative care, such as the most appropriate time to perform surgery or the need for a protective stoma. More studies are still needed to clarify whether that exposure is harmless, and to avoid unnecessary interruptions in biological treatment, delays in surgery and unnecessary ostomies.

Pregnancy and newborn care

Except for certolizumab, biological drugs pass through the umbilical cord which results in potential exposure of the fetus and newborns to these drugs. Discontinuing a biologic agent before the third trimester can limit that exposure. However, continuing these drugs during the entire pregnancy appears to be safe, and interruption of biological therapy may increase the chances of relapse, with negative consequences for both mother and fetus. Likewise, a drug holiday may increase the risk of secondary loss of response in the postpartum period. Although withholding biologic therapy in the third trimester has been associated with an increased risk of flaring during pregnancy, this approach may be considered safe when guided by TDM in selected pregnant women.74

Although biologic therapy seems not to increase the risk of serious infections in the first years of children exposed in utero to anti-TNF, vedolizumab or ustekinumab, these drugs can impact the effectiveness and safety of vaccinations in the first year of life.74 For this reason, European Crohn´s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines recommend that in children exposed in utero to biologics, live attenuated vaccines should be withheld within the first year of life or until the biologic is no longer detectable in the infant’s blood.74

Conclusion

The positive association between trough concentration and clinical outcomes and drug concentrations and antidrug antibodies help guide decisions. Reactive TDM is more cost-effective and more appropriately directs therapy than empiric dose escalation. Proactive TDM for optimizing anti-TNF therapy optimizes outcomes when compared to standard of care and should likely be applied during induction. More data are needed on how to best utilize reactive and proactive TDM for non-TNF biologics.

Figure legend

Figure 1 – Factors associated with drug clearance of all biologics in IBD patients. Anti-TNF: anti-tumor necrosis factor; VDZ: vedolizumab; UST: ustekinumab; RZK: rizankizumab; MKZ: mirikizumab; CRP: C-reactive protein; fCAL: calprotectin fecal; Cr Clear.: creatinine clearance.

Figure 2 – Algorithm for reactive TDM.

Table 1: Suggested optimal trough level for biologic agents in different phases of the treatment.4, 32

* For intravenous formulation

Figure 3 - Algorithm designed to guide therapeutic decisions based on TDM.75

Figure 4 - Algorithm used to guide anti-TNF reintroduction after a drug holiday.70, 71

References

1. Wu JF. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Biologics for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: How, When, and for Whom? Gut Liver. 2022 Jul 15;16(4):515–24.

2. Vande Casteele N, Herfarth H, Katz J, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the Role of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep;153(3):835-857.e6.

3. Kennedy NA, Heap GA, Green HD, Hamilton B, Bewshea C, Walker GJ, et al. Predictors of anti-TNF treatment failure in anti-TNF-naive patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease: a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May;4(5):341–53.

4. Irving PM, Gecse KB. Optimizing Therapies Using Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Current Strategies and Future Perspectives. Gastroenterology. 2022 Apr;162(5):1512–24.

5. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013 Aug 22;369(8):711–21.

6. Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, et al. Vedolizumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013 Aug 22;369(8):699–710.

7. Adedokun OJ, Xu Z, Gasink C, Jacobstein D, Szapary P, Johanns J, et al. Pharmacokinetics and Exposure Response Relationships of Ustekinumab in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018 May;154(6):1660–71.

8. Verstockt B, Dreesen E, Noman M, Outtier A, Van den Berghe N, Aerden I, et al. Ustekinumab Exposure-outcome Analysis in Crohn’s Disease Only in Part Explains Limited Endoscopic Remission Rates. J Crohns Colitis. 2019 Jul 25;13(7):864–72.

9. Deyhim T, Cheifetz AS, Papamichael K. Drug Clearance in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated with Biologics. J Clin Med. 2023 Nov 16;12(22):7132.

10. Lefevre PLC, Shackelton LM, Vande Casteele N. Factors Influencing Drug Disposition of Monoclonal Antibodies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Implications for Personalized Medicine. BioDrugs. 2019 Oct 12;33(5):453–68.

11. Ordás I, Mould DR, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Anti-TNF Monoclonal Antibodies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pharmacokinetics-Based Dosing Paradigms. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Apr 22;91(4):635–46.

12. Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Ford J, Hernandez D, Johanns J, Hu C, et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Dec 16;65(12):1211–28.

13. Brandse JF, Mould D, Smeekes O, Ashruf Y, Kuin S, Strik A, et al. A Real-life Population Pharmacokinetic Study Reveals Factors Associated with Clearance and Immunogenicity of Infliximab in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Apr;23(4):650–60.

14. Ponce-Bobadilla AV, Stodtmann S, Chen MJ, Winzenborg I, Mensing S, Blaes J, et al. Assessing the Impact of Immunogenicity and Improving Prediction of Trough Concentrations: Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Adalimumab in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2023 Apr 11;62(4):623–34.

15. Vande Casteele N, Mould DR, Coarse J, Hasan I, Gils A, Feagan B, et al. Accounting for Pharmacokinetic Variability of Certolizumab Pegol in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017 Dec 28;56(12):1513–23.

16. Dreesen E, Kantasiripitak W, Detrez I, Stefanović S, Vermeire S, Ferrante M, et al. A Population Pharmacokinetic and Exposure–Response Model of Golimumab for Targeting Endoscopic Remission in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Aug 2;

17. Zhao L, Ji P, Li Z, Roy P, Sahajwalla CG. The Antibody Drug Absorption Following Subcutaneous or Intramuscular Administration and Its Mathematical Description by Coupling Physiologically Based Absorption Process with the Conventional Compartment Pharmacokinetic Model. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2013 Mar 20;53(3):314–25.

18. Schreiber S, Ben-Horin S, Leszczyszyn J, Dudkowiak R, Lahat A, Gawdis-Wojnarska B, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial: Subcutaneous vs Intravenous Infliximab CT-P13 Maintenance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2340–53.

19. Rosario M, Polhamus D, Chen C, Sun W, Dirks N. P490 A vedolizumab population pharmacokinetic model including intravenous and subcutaneous formulations for patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2019 Jan 25;13(Supplement_1):S357–S357.

20. Wang Z, Verstockt B, Sabino J, Vermeire S, Ferrante M, Declerck P, et al. Population pharmacokinetic‐pharmacodynamic model‐based exploration of alternative ustekinumab dosage regimens for patients with Crohn’s disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022 Jan 19;88(1):323–35.

21. Adedokun OJ, Xu Z, Gasink C, Kowalski K, Sandborn WJ, Feagan B. Population Pharmacokinetics and Exposure–Response Analyses of Ustekinumab in Patients With Moderately to Severely Active Crohn’s Disease. Clin Ther. 2022 Oct;44(10):1336–55.

22. Xu Y, Hu C, Chen Y, Miao X, Adedokun OJ, Xu Z, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics and Exposure‐Response Modeling Analyses of Ustekinumab in Adults With Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2020 Jul 5;60(7):889–902.

23. Suleiman AA, Goebel A, Bhatnagar S, D’Cunha R, Liu W, Pang Y. Population Pharmacokinetic and <scp>Exposure–Response</scp> Analyses for Efficacy and Safety of Risankizumab in Patients With Active Crohn’s Disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023 Apr 20;113(4):839–50.

24. Chua L, Friedrich S, Zhang XC. Mirikizumab Pharmacokinetics in Patients with Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis: Results from Phase III LUCENT Studies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2023 Oct 23;62(10):1479–91.

25. Martins C de A, Garcia KS, Queiroz NSF. Multi-utility of therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Jul 28;9.

26. Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, Munck LK, Fallingborg J, Christensen LA, et al. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut. 2014 Jun;63(6):919–27.

27. Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, Munck LK, Fallingborg J, Christensen LA, et al. Individualized Therapy Is a Long-Term Cost-Effective Method Compared to Dose Intensification in Crohn’s Disease Patients Failing Infliximab. Dig Dis Sci. 2015 Sep 12;60(9):2762–70.

28. Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, Gerson L, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep;153(3):827–34.

29. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 27;114(3):384–413.

30. Lichtenstein GR, Loftus E V, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn’s Disease in Adults. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018 Apr;113(4):481–517.

31. van Rheenen PF, Aloi M, Assa A, Bronsky J, Escher JC, Fagerberg UL, et al. The Medical Management of Paediatric Crohn’s Disease: an ECCO-ESPGHAN Guideline Update. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Feb 1;15(2):171–94.

32. Cheifetz AS, Abreu MT, Afif W, Cross RK, Dubinsky MC, Loftus E V., et al. A Comprehensive Literature Review and Expert Consensus Statement on Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Biologics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;116(10):2014–25.

33. Mitrev N, Vande Casteele N, Seow CH, Andrews JM, Connor SJ, Moore GT, et al. Review article: consensus statements on therapeutic drug monitoring of anti‐tumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Dec 13;46(11–12):1037–53.

34. Vande Casteele N, Abreu MT, Flier S, Papamichael K, Rieder F, Silverberg MS, et al. Patients With Low Drug Levels or Antibodies to a Prior Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Are More Likely to Develop Antibodies to a Subsequent Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2022 Feb;20(2):465-467.e2.

35. Costable NJ, Borman ZA, Ji J, Dubinsky MC, Ungaro RC. Prior Immunogenicity to Anti-TNF Biologics Is Not Associated with Increased Anti-drug Antibodies to Vedolizumab or Ustekinumab. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Jun 21;67(6):2480–4.

36. Steenholdt C, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, Ainsworth MA. Clinical Implications of Measuring Drug and Anti-Drug Antibodies by Different Assays When Optimizing Infliximab Treatment Failure in Crohn’s Disease: Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014 Jul;109(7):1055–64.

37. Van Stappen T, Vande Casteele N, Van Assche G, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Gils A. Clinical relevance of detecting anti-infliximab antibodies with a drug-tolerant assay: post hoc analysis of the TAXIT trial. Gut. 2018 May;67(5):818–26.

38. Battat R, Lukin D, Scherl EJ, Pola S, Kumar A, Okada L, et al. Immunogenicity of Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists and Effect of Dose Escalation on Anti-Drug Antibodies and Serum Drug Concentrations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 Aug 19;27(9):1443–51.

39. Strik AS, van den Brink GR, Ponsioen C, Mathot R, Löwenberg M, D’Haens GR. Suppression of anti‐drug antibodies to infliximab or adalimumab with the addition of an immunomodulator in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Apr 23;45(8):1128–34.

40. Imbrechts M, Van Stappen T, Compernolle G, Tops S, Gils A. Anti-infliximab antibodies: How to compare old and new data? J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2020 Jan;177:112842.

41. Papamichail K, Cheifetz AS. Mistakes in therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in IBD and how to avoid them. UEG Education. 2023;23:12–8.

42. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, Hendy PA, Smith PJ, Limdi JK, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019 Dec;68(Suppl 3):s1–106.

43. Annese V, Nathwani R, Alkhatry M, Al-Rifai A, Al Awadhi S, Georgopoulos F, et al. Optimizing biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a Delphi consensus in the United Arab Emirates. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan 22;14:175628482110653.

44. Papamichael K, Vande Casteele N, Jeyarajah J, Jairath V, Osterman MT, Cheifetz AS. Higher Postinduction Infliximab Concentrations Are Associated With Improved Clinical Outcomes in Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease: An ACCENT-II Post Hoc Analysis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2021 May;116(5):1007–14.

45. Papamichael K, Casteele N Vande, Ferrante M, Gils A, Cheifetz AS. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring During Induction of Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Sep;23(9):1510–5.

46. Dreesen E, D’Haens GR, Baert FJ, Pariente B, Bouhnik Y, Van Der Woude CJ, et al. Mo1841 - Infliximab Exposure Predicts Superior Endoscopic Outcomes in Patients with Active Crohn’s Disease: Pharmacokineticpharmacodynamic Analysis of Tailorix. Gastroenterology. 2018 May;154(6):S-821.

47. Verstockt B, Moors G, Bian S, Van Stappen T, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of early adalimumab serum levels on immunogenicity and long‐term outcome of anti‐TNF naive Crohn’s disease patients: the usefulness of rapid testing. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Oct 15;48(7):731–9.

48. Bar‐Yoseph H, Levhar N, Selinger L, Manor U, Yavzori M, Picard O, et al. Early drug and anti‐infliximab antibody levels for prediction of primary nonresponse to infliximab therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Jan 9;47(2):212–8.

49. Lega S, Phan BL, Rosenthal CJ, Gordon J, Haddad N, Pittman N, et al. Proactively Optimized Infliximab Monotherapy Is as Effective as Combination Therapy in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Jan 1;25(1):134–41.

50. Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, Ballet V, Compernolle G, Van Steen K, et al. Trough Concentrations of Infliximab Guide Dosing for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015 Jun;148(7):1320-1329.e3.

51. Papamichael K, Rakowsky S, Rivera C, Cheifetz AS, Osterman MT. Infliximab trough concentrations during maintenance therapy are associated with endoscopic and histologic healing in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb 6;47(4):478–84.

52. Papamichael K, Rakowsky S, Rivera C, Cheifetz AS, Osterman MT. Association Between Serum Infliximab Trough Concentrations During Maintenance Therapy and Biochemical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Remission in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018 Sep 15;24(10):2266–71.

53. Assa A, Matar M, Turner D, Broide E, Weiss B, Ledder O, et al. Proactive Monitoring of Adalimumab Trough Concentration Associated With Increased Clinical Remission in Children With Crohn’s Disease Compared With Reactive Monitoring. Gastroenterology. 2019 Oct;157(4):985-996.e2.

54. Juncadella A, Papamichael K, Vaughn BP, Cheifetz AS. Maintenance Adalimumab Concentrations Are Associated with Biochemical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Nov 13;63(11):3067–73.

55. Samaan MA, Pavlidis P, Digby-Bell J, Johnston EL, Dhillon A, Paramsothy R, et al. Golimumab: early experience and medium-term outcomes from two UK tertiary IBD centres. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2018 Jul;9(3):221–31.

56. Syversen SW, Jørgensen KK, Goll GL, Brun MK, Sandanger Ø, Bjørlykke KH, et al. Effect of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring vs Standard Therapy During Maintenance Infliximab Therapy on Disease Control in Patients With Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. JAMA. 2021 Dec 21;326(23):2375.

57. Pauwels RWM, van der Woude CJ, Nieboer D, Steyerberg EW, Casanova MJ, Gisbert JP, et al. Prediction of Relapse After Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Cessation in Crohn’s Disease: Individual Participant Data Meta-analysis of 1317 Patients From 14 Studies. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2022 Aug;20(8):1671-1686.e16.

58. Zhang B, Gulati A, Alipour O, Shao L. Relapse From Deep Remission After Therapeutic De-escalation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Oct 5;14(10):1413–23.

59. Lucidarme C, Petitcollin A, Brochard C, Siproudhis L, Dewitte M, Landemaine A, et al. Predictors of relapse following infliximab de‐escalation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the value of a strategy based on therapeutic drug monitoring. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Jan 27;49(2):147–54.

60. Petitcollin A, Brochard C, Siproudhis L, Tron C, Verdier M, Lemaitre F, et al. Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Infliximab Influence the Rate of Relapse After De‐Escalation in Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Sep 29;106(3):605–15.

61. Drobne D, Bossuyt P, Breynaert C, Cattaert T, Vande Casteele N, Compernolle G, et al. Withdrawal of Immunomodulators After Co-treatment Does Not Reduce Trough Level of Infliximab in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015 Mar;13(3):514-521.e4.

62. Melmed GY, Irving PM, Jones J, Kaplan GG, Kozuch PL, Velayos FS, et al. Appropriateness of Testing for Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Agent and Antibody Concentrations, and Interpretation of Results. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016 Sep;14(9):1302–9.

63. Normatov I, Fluxa D, Wang JD, Ollech JE, Gulotta GE, Patel S, et al. Real-World Experience With Proactive Therapeutic Drug Monitoring During Infliximab Reintroduction. Crohns Colitis 360. 2021 Jul 1;3(3).

64. Noor NM, Sousa P, Bettenworth D, Gomollón F, Lobaton T, Bossuyt P, et al. ECCO Topical Review on Biological Treatment Cycles in Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2023 Jul 5;17(7):1031–45.

65. Yarur AJ, Abreu MT. Back to the Beginning: Restarting Infliximab in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients With Prior Loss of Response. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014 Sep;12(9):1482–4.

66. Yang S, Yang S, Kwon Jo Y, Kim S, Jung Chang M, Choi J, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of infliximab retreatment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021 Jan 8;12:204062232110419.

67. Baert F, Drobne D, Gils A, Vande Casteele N, Hauenstein S, Singh S, et al. Early Trough Levels and Antibodies to Infliximab Predict Safety and Success of Reinitiation of Infliximab Therapy. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014 Sep;12(9):1474-1481.e2.

68. van Wassenaer EA, Meester VL, Kindermann A, Koot BGP, Benninga MA, de Meij TGJ. Premedication with intravenous steroids does not influence the incidence of infusion reactions following infliximab infusions in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients—a case-control study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019 Oct 22;75(10):1445–50.

69. Fumery M, Tilmant M, Yzet C, Brazier F, Loreau J, Turpin J, et al. Premedication as primary prophylaxis does not influence the risk of acute infliximab infusion reactions in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2019 Apr;51(4):484–8.

70. Fluxa D, Quintero MA, De la Torre B, Solis NI, Damas OM, Deshpande A, et al. Tu1834 – A Protocol for Safe Reintroduction of Infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2019 May;156(6):S-1142-S-1143.

71. Normatov I, Wang JD, Gulotta GE, Patel S, Rubin DT. Mo1890 – Using Therapeutic Drug Monitoring to Predict Success of Restarting Infliximab Therapy After a Drug Holiday in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2019 May;156(6):S-876.

72. Plevris N, Jenkinson PW, Arnott ID, Jones GR, Lees CW. Higher anti-tumor necrosis factor levels are associated with perianal fistula healing and fistula closure in Crohn’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jan;32(1):32–7.

73. Cohen BL, Fleshner P, Kane S V., Herfarth HH, Palekar N, Farraye FA, et al. Prospective Cohort Study to Investigate the Safety of Preoperative Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor Exposure in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Undergoing Intra-abdominal Surgery. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jul;163(1):204–21.

74. Torres J, Chaparro M, Julsgaard M, Katsanos K, Zelinkova Z, Agrawal M, et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis Guidelines on Sexuality, Fertility, Pregnancy, and Lactation. J Crohns Colitis. 2023 Jan 27;17(1):1–27.

75. Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2019 Jul;35(4):302–10.