“肺结核患者出现腹泻是一种致命的症状。”

— 希波克拉底, 格言篇 5.14

“腹部结核病无法确诊,因为这种疾病与许多其他腹部疾病相似,并且组织学确认可能是模棱两可的。”

— Joseph Walsh, Transactions of the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis 1909;5:217–22

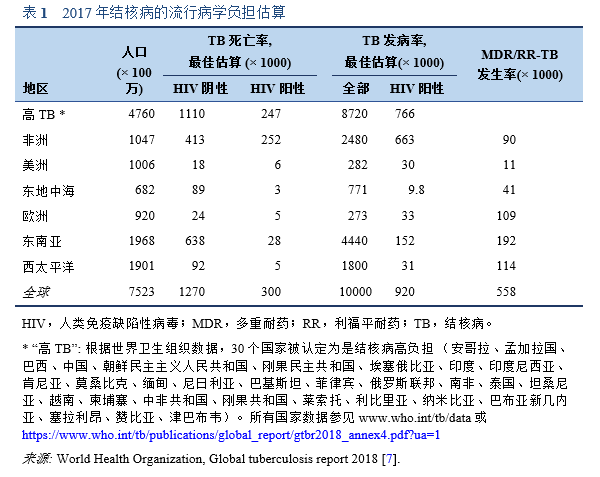

结核病(Tuberculosis,TB)是一种由结核分枝杆菌引起的传染病,通常引起肺结核。结核病是全球第九大最常见的死因,是单一传染源造成死亡的首要原因,排在人类免疫缺陷病毒/获得性免疫缺陷综合征(HIV/AIDS)之前。

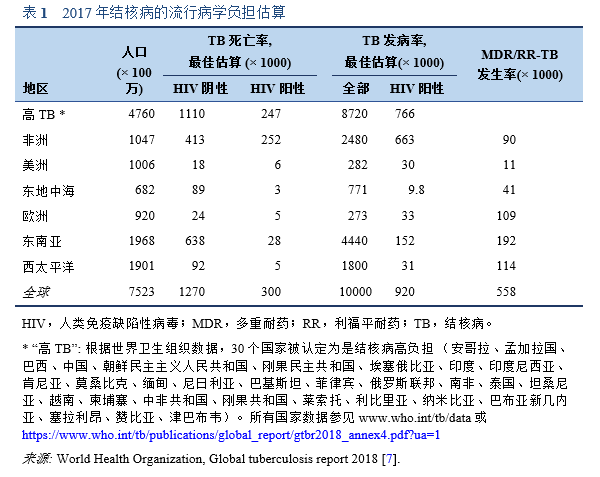

2017年,有1000万人患结核,160万人死于结核,其中包括30万HIV感染者—结核是HIV阳性患者的头号杀手[1]。

- 世界上大约四分之一的人口患有潜伏性结核。

- 感染结核病菌的人一生中患结核病的风险为5–15%。然而,免疫系统受损的人,例如感染HIV、营养不良、患糖尿病、服用免疫抑制剂和吸烟的人,患病风险要高得多。

- 多重耐药结核病(Multidrug-resistant TB, MDR-TB)仍然是一个公共卫生问题和健康安全威胁。世界卫生组织(WHO)估计有55.8万名新患者对利福平—最有效的一线药物—产生耐药性,其中82%有MDR-TB。

- 在全球范围内,结核的发病率正以每年2%的速度下降。

- 2000年至2019年间,通过结核的诊断和治疗,挽救了约6000万人的生命[1]。

与肺结核相比,腹部结核并不常见。在美国,胃肠道结核占了肺外病例的2.5% [2]。

- 淋巴结病是肺外结核病(Extrapulmonary tuberculosis,EPTB)最常见的表现,无论是在HIV感染还是HIV血清阴性的患者中。

- 胸膜结核约占所有肺外结核病例的20%。

- 在美国,泌尿生殖系统结核占所有肺外结核病例的10-15%。

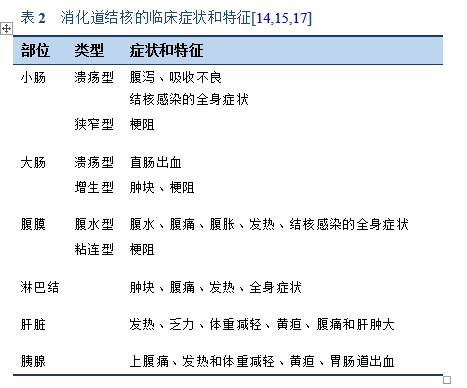

结核的非特异性临床表现可能与其他胃肠道疾病相似,在结核病流行地区可能表现为急腹症到慢性腹痛不等,因此,早期诊断仍然困难。虽然有些患者可能从抗结核治疗中获益,但有患者可能会出现诸如狭窄、梗阻、瘘管或者穿孔等外科问题而可能需要手术干预。

HIV感染是发生结核的主要危险因素,腹膜结核因其隐匿性和非特异性症状而成为免疫功能低下患者的真正医学挑战。

虽然结核可累及消化道的任何部位,但最常受累的部位是回盲部、回肠和结肠。回盲部是最常受结核感染的区域。其原因包括该区域淋巴组织密度高、肠道运输缓慢和胆汁酸浓度低[3]。

所有不明原因的渗出性腹水都需要考虑结核性腹膜炎的可能。腹部结核感染的其他部位还有脾脏、肝脏和淋巴结[3–6]。

1.1 关于WGO分级管理

WGO分级管理:根据可获得资源对风险和疾病的诊断、治疗和管理进行分级处理。

无论是“发展中”、“半发达”或“发达”地区,WGO指南和分级管理旨在突出针对所有地区的合适的、与环境和资源相关的处置方式。WGO分级管理是环境相关的,环境不能简单定义为资源可用性。

这里提出的胃肠道结核诊疗的分级管理是关键,代表了本文最重要的部分。特别强调的内容按金标准、中等资源和低级别资源分类。

关于“胃肠道结核的分级诊断”,请参见下文3.1节。

1.2 定义

- 腹部结核:发生在胃肠道和腹腔内其他脏器上的结核,食管结核除外。

- 肠结核:非腹膜性的胃肠道结核。

- 腹膜结核: 发生在腹膜的结核。

1.3 流行病学

1.3.1 世界卫生组织(WHO)2018年全球结核病报告[1,7]

- 结核病在世界各地都有发生。2017年,新发结核病例最多的地区是东南亚和西太平洋,占所有新发病例的62%,其次是非洲地区,占新发病例的25%。

- 所有国家和各年龄组都有病例,但总的来说,90%的患者是成年人( 15岁),9%是HIV感染者(其中72%在非洲)。

- 2017年,87%的新结核病例发生在结核病高负担的30个国家中,其中三分之二发生在8个国家:印度(27%)、中国(9%)、印度尼西亚(8%)、菲律宾(6%)、巴基斯坦(5%)、尼日利亚(4%)、孟加拉国(4%)和南非(3%)。

- 仅有6%的全球病例发生在WHO欧洲地区(3%)和 WHO美洲地区(3%)。

- 各国结核病流行的严重程度差别很大。2017年,大多数高收入国家每10万人口中新发病例少于10例,30个结核病高负担国家中的大多数国家每10万人口中新发150-400例,少数国家(包括莫桑比亚、菲律宾和南非)每10万人口中新发大于500例。

- 耐药结核病仍是一场公共卫生危机。以下三个国家的多重耐药/利福平耐药结核(MDR/RR-TB)病例占全球病例的近一半:印度(24%)、中国(13%)和俄罗斯联邦(10%)。

- 在全球范围内,3.5%的新发结核患者和18%的既往治疗患者有MDR/RR-TB。前苏联国家所占比例最高(在既往治疗患者中占比>50%)。2017年,在MDR-TB患者中,大约有8.5%(95%CI,6.2%-11%)的患者为广泛耐药结核(Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis,XDR-TB)。

- 由于移民、HIV和多重耐药性结核的发展,西方国家的结核病地理分布正在发生变化[8]。

- 在一些西方国家,腹部结核大多数是“进口”而不是“本土”的。

- 欧洲克罗恩病和结肠炎组织(ECCO)指南指出,在结核病高发国家呆一段时间也会增加个人患病风险[9]。

肠结核(Intestinal tuberculosis,ITB)的发病率随着结核病流行率的整体增加而增加。在欧盟,五分之一的结核患者患有肺外结核[10]。在过去的几十年里,克罗恩病(Crohn’s disease,CD)的发病率在世界范围内也有所增加,包括常规报道该病罕见的地区[11]。

1.4 发病机制和危险因素

结核病在贫穷和人口过多的地方容易传播;在约17亿感染结核分枝杆菌(Mycobacterium tuberculosis,MTB)的人中,有5-15%会在有生之年发展为有表现的临床结核病[12]。

感染HIV的人患结核病的可能性高得多,而有以下这些危险因素的人同样具有患病高风险[13]:

- 其他原因的免疫抑制—糖皮质激素治疗、免疫抑制或化疗、抗肿瘤坏死因子(TNF)药物治疗或其他生物治疗,以及接受持续非卧床腹膜透析的患者。

- 慢性衰竭性疾病—糖尿病、血液病和慢性肺病,尤其是矽肺。

- 营养不良,有潜在恶性肿瘤、肝硬化、酗酒。

- 老年患者。

- 被监禁和收容有结核病风险的个人。

- 结核病高发国家旅行史。

肺外结核病在HIV感染患者中更常见:

- 2016年,在全球范围内,57%的已通报的结核病患者有记录在案的HIV阳性检测结果,较2015年的55%有所上升。在 HIV相关结核负担最重的WHO非洲地区,82%的结核病患者有记录在案的HIV阳性检测结果(较2015年的81%上升)[12]。

- 结核病的诊断可能比AIDS的诊断早几个月;结核病常在AIDS患者中呈播散性,进展迅速,死亡率高[14]。

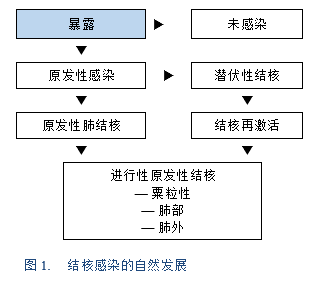

腹部结核可因以下情况发生:

- 休眠的原发性胃肠道病灶的再激活:

— 源于儿童时期原发性感染时肺部病灶的血行传播。

— 或是由吞下的杆菌通过巨噬细胞经淋巴管运输到肠系膜淋巴结引起,在肠系膜淋巴结内它们保持休眠状态。

- 从活动的肺部病灶中摄入杆菌。

- 其他器官的活动性结核的血行传播。

- 邻近器官的直接传播。

- 摄入感染的牛奶:

— 饮用未经巴氏灭菌的牛奶,特别是在某些地区儿童牧羊时(例如巴基斯坦高地地区和中亚其他地区),是导致腹部结核的一个病因。

— 牛结核病的消失、牛奶的巴士灭菌法、以及发展中国家在食用前煮沸牛奶的做法,使得这一病因在西方国家很少见。

潜伏期结核病灶的再激活可能是由高龄、HIV/AIDS感染、抗 TNF治疗、营养不良、体重减轻、酗酒、糖尿病、慢性肾衰和其他疾病造成的免疫抑制导致的[12,14,15]。

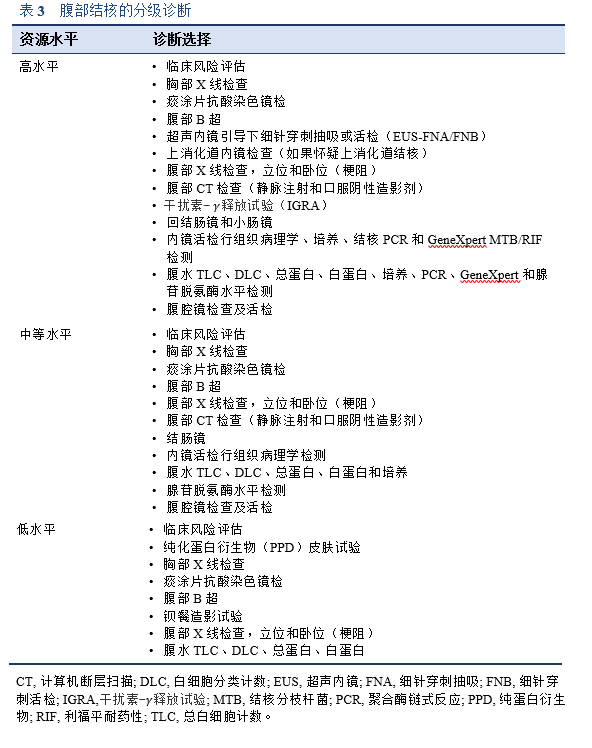

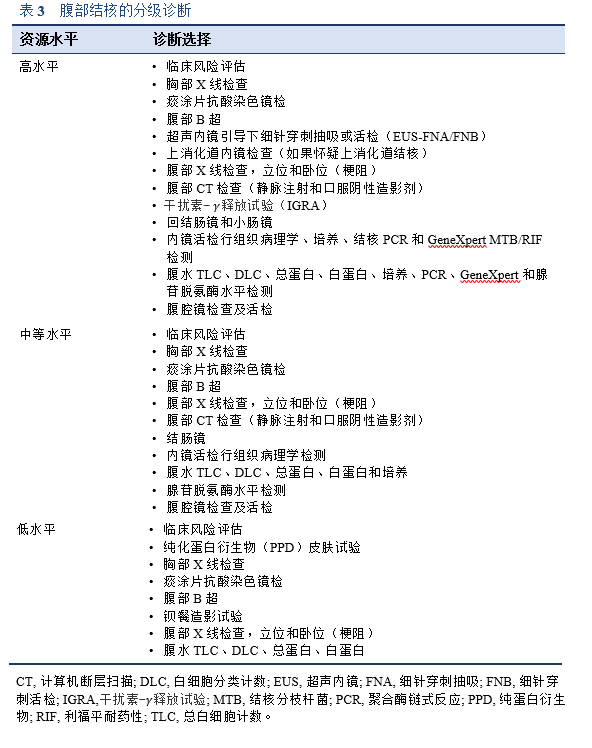

3.1 胃肠道结核的分级诊断

为不同资源分布和获取水平、不同文化和流行病学情况的国家和区域,提供环境和资源敏感的分级备选方案。

目前尚无潜伏期结核感染和活动性结核早期诊断的金标准;没有一项单一的检测足以诊断所有患者的腹部结核。非HIV患者的腹部结核仍是一个持续的诊断困境,需要高指数的临床怀疑[16]。

在结核病流行地区[4]和发达国家的特定情况下(例如HIV患者和接受免疫抑制剂或生物制剂治疗的患者中),应始终将腹部结核视为急慢性腹部疾病的鉴别诊断之一。

满足以下四个标准中的任何一个,可明确诊断为胃肠道结核[26]:

- 组织培养(结肠活检、淋巴结)结核分枝杆菌阳性

- 典型的抗酸杆菌(Acid-fast bacilli,AFB)组织学表现

- 干酪样肉芽肿的组织学证据

- 活检组织GeneXpert MTB/RIF检测/结核PCR检测阳性

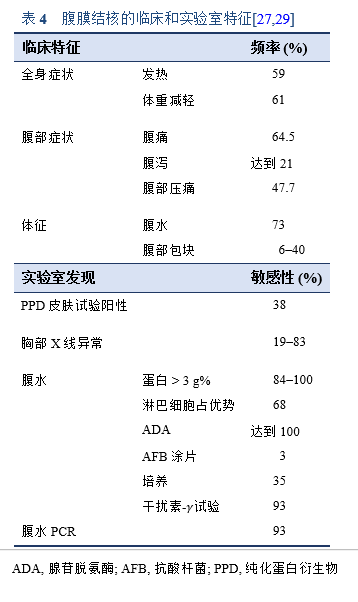

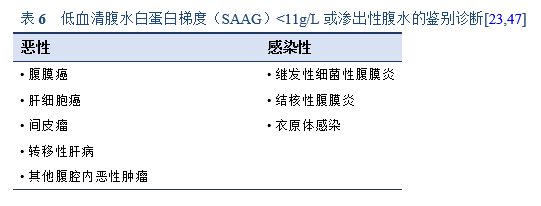

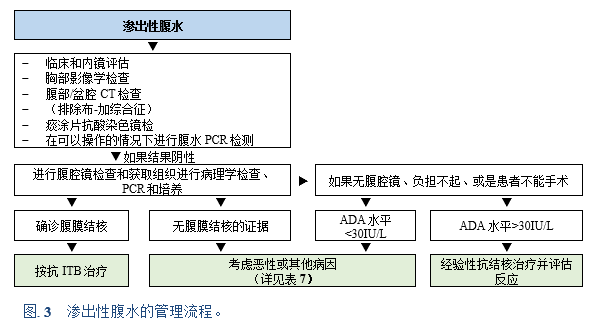

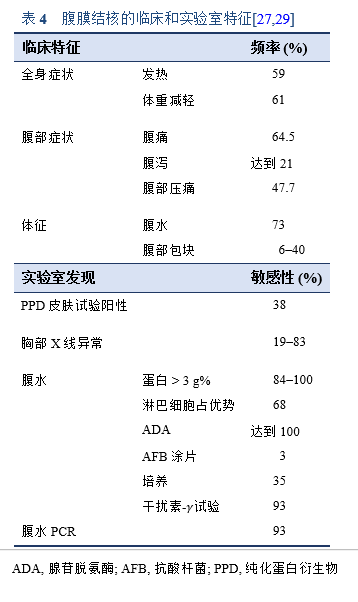

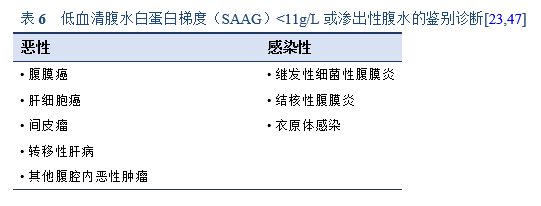

淋巴细胞占优势和/或血清-腹水白蛋白梯度<1.1mg/dL的渗出性腹水(蛋白>2.5g/dL)需鉴别诊断腹膜结核。腺苷脱氨酶水平可升高。微生物学或病理证实仍是诊断的金标准[27]。

肠结核[28]的诊断应基于以下几点:

- 结肠镜检查时至少取8块活检,以进行组织病理学评估。

- 任何抗酸杆菌(AFB)组织检测和培养的阳性结果都具有诊断意义;然而,阴性结果并不排除肠结核的诊断。

- 推荐进行组织PCR检测; 阳性结果意义重大。

— 可以对旧样本进行回顾性检测。

— 阴性结果不排除结核病的诊断。

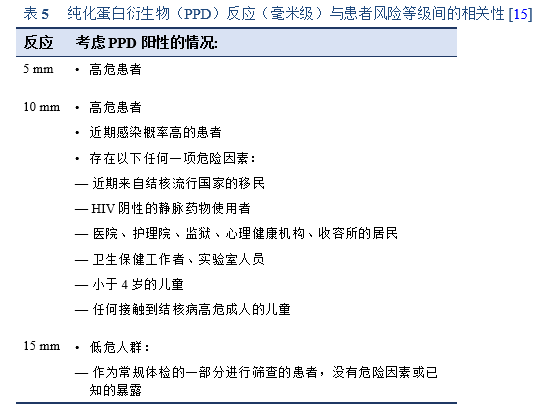

- 阳性PPD试验和阳性IGRA试验。

— PPD试验结果阳性在发展中国家很常见,包括在克罗恩病和其他原因的腹水中。

— PPD或IGRA试验在资源高水平国家用于诊断既往结核暴露情况。

— PPD或IGRA试验不能用于诊断腹部结核,尤其是在高暴露于结核和接种卡介苗(BCG)的发展中国家。

3.2 检查

尽管诊断方法取得了进步,但由于缺乏资金或当地缺乏专业知识,向WHO报告的结核病例中仍有相当大的一部分是通过临床诊断而不是细菌学确诊的。2016年,向WHO报告的肺部病例中,只有不到60%的病例是经细菌学确诊的[12]。

3.2.1 常规实验室检查

常规实验室检查显示50-80%的患者有轻度贫血和血沉增加。白细胞计数通常正常[18]。

3.2.2 影像学检查

口服造影剂的计算机断层扫描(CT)是评估腔内和腔外病变最有帮助的成像方式。它可以显示肠道、肠系膜、腹膜、淋巴结、实质脏器以及腹膜后结构的炎性发展和受累位置及程度[17,18,30]。它可以区分癌性腹水和腹膜结核。有淋巴结坏死表现的可诊断为腹膜结核。如果可行,小肠 CT造影能够发现和描绘出受累的小肠情况。

超声。超声内镜(EUS)有助于对靠近胃肠道管腔的各种病变进行成像,并可以通过EUS引导下的细针穿刺进行抽吸或活检[31]。可对淋巴结、肝脏和胰腺进行靶向活检[32]。EUS对腹膜结核的成像很有帮助[18]。

磁共振成像(MRI)无法检测到淋巴结或肿块内的小钙化灶,也无法帮助鉴别克罗恩病和肠结核。

胸部X线。胸部 X线阴性不能排除腹部结核。

3.2.3 内镜检查

如果病变肠段的位置在内镜可及范围内,内镜活检可能有助于诊断肠结核。直到手术时才最终诊断该疾病的情况并不少见[8]。双气囊小肠镜可能有助于获得活检。对于没有明显溃疡的十二指肠浸润病灶,采用圈套息肉摘除的方式可能有助于获得更好的活检[25]。

- 如果在活检组织上找到抗酸杆菌或是干酪样肉芽肿,则可快速诊断肠结核。

- 对于腹膜结核,应进行内镜检查以排除原发性消化道肿瘤(癌性腹水)。

- 小肠镜和胶囊内镜可用于检查小肠疾病。对于疑似狭窄的患者,必须避免胶囊内镜检查。

3.2.4 腹腔镜检查

腹腔镜活检可用于诊断腹膜结核,但其在肠结核中的作用尚不明确[17]。腹腔镜直视活检可实现快速、特异的诊断[8]。

- 诊断性腹腔镜检查发现包括:腹膜增厚、腹水、白色结节、淋巴结、纤维化粘连和肝肿大。

- 肠道脂肪包裹在肠结核中不常见[33,34],而提示需考虑克罗恩病。

3.2.5 病理学检查

结核病例的活检组织会有抗酸杆菌或干酪样肉芽肿,但抗酸杆菌染色缺乏敏感性和特异性。很难完全直接地区分克罗恩病和结核病。尽管很罕见,但这两种疾病可以共存,尤其是在进行生物治疗期间。

通过内镜和黏膜活检很难诊断肠结核,因为病变是位于黏膜下的,诊断率较低(指通过AFB阳性、结核 PCR阳性、干酪样肉芽肿、或是结核培养阳性)。Pulimood等人描述了缺乏抗酸杆菌和干酪样肉芽肿的黏膜活检标本的一系列组织学特征,以诊断肠结核[35–37]。包括融合性肉芽肿、特定活检部位的多发肉芽肿、大肉芽肿、排列于溃疡内壁的上皮样组织细胞带、黏膜下肉芽肿和不成比例的黏膜下炎症—即黏膜下炎症程度显著超过黏膜炎症程度。

组织病理学发现可能包含非特异性炎症改变:

- 可通过手术、结肠镜检查、CT或超声引导下活检、腹腔镜检查和上消化道内镜检查获取用于组织病理学检查的组织。

- 结核是一种慢性肉芽肿性炎表现的疾病,但给定的样本中可能无肉芽肿。

- 肠道病变可为溃疡性(60%)、增生性(10%)和溃疡增生性(30%)[13]。

- 如果高度怀疑结核病,应将组织送去进行微生物学分析[31] 和分子学检测。

疑似腹部结核的患者,应对其生物学液体进行抗酸染色涂片镜检的细菌学检查。

- 大多数研究显示,痰液、尿液和腹水标本检查的阴性率很高。抗酸染色涂片阳性率随着采样点数量的增加而增加[4]。

- 使用显微镜检查痰液样本确定细菌存在这一技术是在100多年前开发的。在 WHO现在推荐的病例定义中,痰涂片阳性肺结核的诊断至少需要一次阳性结果。

- 不推荐进行粪便AFB染色,因为共生的非结核分枝杆菌会导致肠结核的假阳性诊断。

3.2.6 微生物学检查

基于培养的方法。这是目前的参考标准。这方面需要更加先进的实验室技术;活检组织的MTB培养非常耗时(需要3-8周,甚至12周才能提供结果)[12],并且结果常常是阴性的(准确率约25-35% [17],在其他研究中甚至更低)。

3.2.7 血清学检查结果

快速分子学检测。目前WHO推荐的诊断结核病的唯一快速检测方法是Xpert® MTB/RIF检测(Cepheid,森尼维尔,加利福尼亚州,美国)。

- 它可以在2小时内提供结果,最初(2010年)被推荐用于成人肺结核的诊断。自2013年起,它还被推荐用于儿童和特定形式的肺外结核的诊断。该检测方法比痰涂片镜检有更高的准确性[12]。

- 在诊断腹部结核上,一篇印度综述文章报道了一项来自德里的肠结核患者的研究,提示其肠结核诊断敏感性较低:37名患者中只有3名(8%)Xpert结果阳性。在腹膜结核中,有两篇报道表明Xpert的敏感性也很低,其中一篇在67例疑似病例中阳性的为12例(17.9%),另一篇21例病例中阳性的为4例(19%) [38]。

- 2015年的一项包含36项研究的荟萃分析得出结论,Xpert在检测肺外结核(EPTB)方面具有较高的特异性但敏感性有限。Xpert检测结果阳性可能有助于EPTB病例的快速识别,但阴性结果并不能排除该疾病[39]。

- 2018年一项分析GeneXpert MTB/RIF检测诊断腹部结核的研究(来自21例患者的数据)发现,GeneXpert的敏感性为28.57%,特异性为0%。该研究的作者认为在他们的研究里,在用腹水样本检测腹部结核时,GeneXpert检测的敏感性和特异性均较差。

干扰素- 释放试验(IGRA)。 IGRA基于MTB特异性的免疫显性抗原ESAT-6和CFP10刺激引起的细胞免疫反应,提供了一种替代结核菌素皮肤试验的诊断方法。

IGRA试验选择包括:

- QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube检测 (QFT, Qiagen, 希尔登, 德国),基于全血检测。该检测方法的准确率在使用免疫抑制药物的患者中下降[40]。

- T-SPOT.TB检测 (酶联免疫斑点试验/ELISPOT, Oxford Immunotec, 阿宾登, 英国),基于纯化的外周血单核细胞。

多项研究已经证实了这些检测方法在诊断结核病方面的价值,IGRA检测的出现可能会提高对潜伏性结核感染(LTBI)的识别[41]。

这些检测方法的主要优势是:

- 其不受既往接种卡介苗的影响。

- 其与大多数非结核分枝杆菌无交叉反应。

- 其只需要一次就诊就可完成。

不足是:

- 检查费用为100美元或是更高,可能会妨碍低收入国家推荐这些检测方法。

- 需要专门配备的实验室、训练有素的人员和侵入性程序。

- IGRA不能区分活动性和潜伏性结核。

- IGRA结果阴性不能排除LTBI。

- 这些检测不能预测潜伏性结核病的进展[11]。

虽然仍难以确定IGRAs和结核菌素皮肤试验(Tuberculin skin test,TST)之间的优越性,但两者均受到免疫抑制治疗的负面影响。因此,应考虑在开始免疫抑制治疗前进行筛查。在抗-TNF治疗前,所有患者都必须接受筛查[40]。

IGRA可用作总体风险评估的一部分,以识别需要进行预防性治疗的个体(例如,免疫功能低下者、儿童、密切接触者和近期有暴露的个体)[42],但由于上述的不足,IGRA不适合大规模的筛查研究,尤其是在儿童中。

检测腹水中的干扰素- 水平可能是未来用于诊断腹膜结核的一项技术[27]。

欧洲疾病预防控制中心(ECDC)发布了以下关于使用干扰素- 释放试验支持结核诊断的指南[42]:

- IGRAs不能取代诊断活动性结核病的标准诊断方法(包括微生物学、分子检测、临床和影像学评估)。

- 在与诊断活动性结核病的标准方法结合时,IGRAs在大多数临床情况下没有任何附加价值。

- 然而,基于有限的证据,在某些临床情况下(例如,肺外结核患者、痰液抗酸杆菌阴性和/或结核分枝杆菌培养阴性的患者、儿童结核病诊断、或非结核分枝杆菌感染的鉴别诊断),IGRAs可作为诊断流程中的一部分以提供补充信息。阴性的IGRA结果不排除活动性结核病。

- 根据可用结果中的用于评估进展的阳性预测值(PPV)结果,并考虑到研究的低统计学功效以及研究数量少的情况,IGRAs可作为总体风险评估的一部分,以识别需要进行预防性治疗的个体(例如,免疫功能低下者、儿童、密切接触者和近期有暴露的个体)。

- 同样地,尽管现有研究存在局限性,IGRAs在评估进展时的高阴性预测值(NPV)表明,在总体风险评估的背景下,在检测时IGRAs阴性的免疫功能正常的患者发展为活动性结核的可能性很低。因此,可以在这种情况下使用IGRAs。

- 需要注意的是,特别是在高危人群和特定情况下,IGRA阴性并不能排除LTBI。

3.2.8 聚合酶链式反应检测

PCR. 对肠结核(ITB)患者的内镜或手术活检标本进行结核PCR检测,在诊断ITB时有很高的准确度,特异性高达95%,准确度为82.6%[17]。

- 2017年的一项荟萃分析得出结论,MTB的PCR检测是一种有前景且高度特异性的诊断方法,可区分ITB和克罗恩病。然而,由于检测的低敏感性,阴性结果不能排除ITB[43]。

- 腹水PCR检测可能有助于腹膜结核诊断[29]。

3.2.9 结核菌素皮肤试验

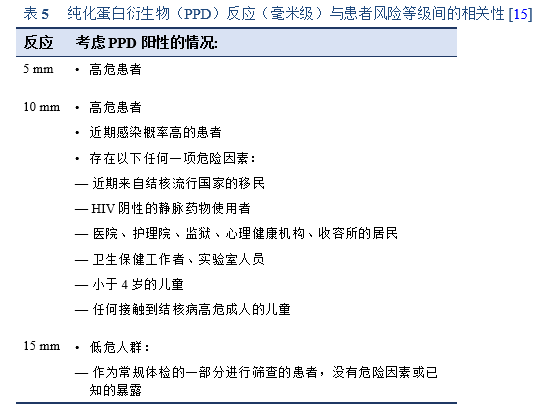

PPD. 纯化蛋白衍生物(PPD)试验是结核菌素皮肤试验(TST)的升级版。它是基于结核分枝杆菌培养滤液中的蛋白成分,用于诊断(潜伏)结核感染。

- 皮内注射0.1mL的PPD,48-72小时后观察结果。

- 如果第一次检测结果为阴性,可在1-3周后重新检测。

- 大约70%的患者PPD试验呈阳性,但阴性结果并不能排除该病。

假阴性 PPD反应可能是由于:

- 活动性疾病期间启动的细胞因子。

- 其他原因导致的免疫低下(例如HIV和其他病毒感染)造成的无反应。

- 严重的,例如播散性结核。

- 所有的免疫抑制疗法。

- 营养不良。

PPD皮肤试验对ITB的诊断价值尚不明确,其结果受到测试人群结核患病率的影响[13,15,17]:

- 在高流行区(>20例/10万人/年)的阳性检测结果更有可能提示真正的结核感染,而在低流行区(<10例/10万人/年)则可能是假阳性。

- 在世界上仍进行卡介苗接种的地方,TST的假阳性率非常高。

对于 PPD检测时免疫反应弱的患者,其诊断价值也是有限的。这种较弱的免疫反应可能是由于:

— HIV感染

— 原发性和播散性结核病

— 使用糖皮质激素或免疫调节药物

3.2.10 腺苷脱氨酶

腺苷脱氨酶(Adenosine deaminase,ADA)是结核性腹水的可靠酶标记物。ADA的临界值在36-40IU/L对诊断腹膜结核有很高的敏感性(100%)和特异性(97%)[23,44]。

- 腹水ADA活性评估是诊断结核性腹膜炎的一种相对敏感和特异的检查—在一篇包含16项研究的荟萃分析中,其诊断结核性腹膜炎的敏感性和特异性汇总数据分别为0.93(95% CI, 0.89-0.95)和0.96(95% CI, 0.94-0.97)[45];在另一项来自17项研究数据的含1797名患者的研究中,敏感性和特异性分别为0.93和0.94[46]。

- 在西方国家,尤其是在高危患者群中,这项检测也可能取代侵入性检查。

- ADA活性测定在医疗中心可能并不普遍使用。

- 特别是在可能无法进行腹腔镜检查和结核病流行的欠发达地区,检测腹水腺苷脱氨酶(ADA)水平是诊断结核性腹膜炎的重要方法[8]。

3.2.11 WHO认可的结核病诊断技术

结核病和耐药性的分子检测技术

- 用于检测肺部、肺外和儿童样本中的结核和利福平耐药的Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra(Cepheid, 森尼维尔,加利福尼亚州,美国)

- 用于检测抗酸杆菌阳性的痰液或MTB培养物中的结核分枝杆菌(MTB)、异烟肼耐药性和利福平耐药性的线性探针检测法(FL-LPA)(Hain Lifescience GmbH,内恩,德国和Nipro,大阪市,日本)

- 用于检测氟喹诺酮类药物和二线注射类药物耐药性的线性探针检测法(SL-LPA) (Hain Lifescience GmbH)

- 用于检测结核的TB LAMP(Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd.,东京,日本)

非分子学检测技术

- Alere Determine TB-LAM(Alere International Ltd.,戈尔韦,爱尔兰)—用于检测严重感染HIV者的结核病

- 干扰素- 释放试验(IGRA)用于诊断潜伏性结核感染(LTBI)(Oxford Immunotec,阿宾登,英国; Qiagen, 日耳曼敦,马里兰州,美国)

基于培养的检测技术

- 商业液体培养系统和快速物种形成技术、

- 在LJ、7H10、7H11和分枝杆菌生长指示管(MGIT)培养基中,采用1%临界比例进行基于培养表型的药敏试验(Drug susceptibility testing,DST)

显微镜技术

3.3 鉴别诊断

3.3.1 腹膜结核

基于病变类型进行鉴别诊断[14]:

- 腹水:需鉴别渗出性腹水的原因—例如癌性腹水、布-加综合征

- 结节:需与癌症鉴别

3.3.2 肠结核

基于病变类型进行鉴别诊断[14]:

- 溃疡型:克罗恩病、溃疡性空肠炎(2型难治性乳糜泻)、热带口炎性腹泻、免疫增生性小肠病

- 狭窄型:克罗恩病、恶性(腺癌和淋巴瘤)、缺血性

- 增生型:盲肠癌、阑尾肿块、阿米巴肉芽肿、放线菌病、克罗恩病

- 穿孔:伤寒、克罗恩病

- 瘘管:克罗恩病

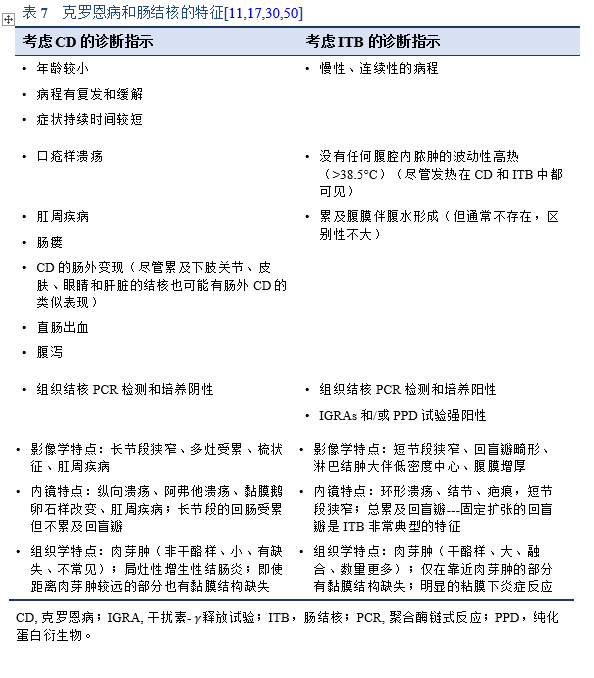

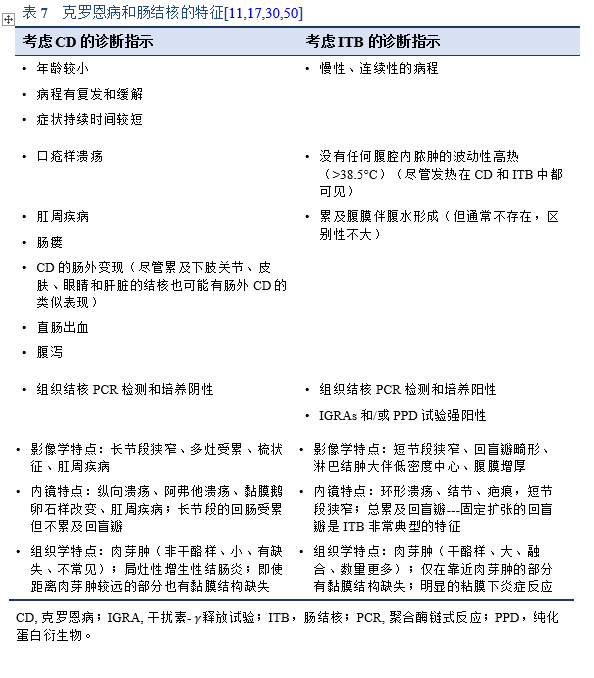

3.3.3 结核病和克罗恩病

克罗恩病(CD)是一种具有明确遗传背景、受多种环境因素影响的特发性炎症性疾病[17]。CD的诊断基于临床特点、内镜特征和组织学特征的整合[26]。

在结核病流行地区,随着结核病发病率的增加,CD的发病率也有所增加[17,48,49]。

- 沙特阿拉伯的一项研究报告称,在过去的20年里,CD的平均年发病率从0.32/10万上升到1.66/10万;在同一地区的儿童人群中也发现了类似的结果。

- 在黎巴嫩一项2000年到2004年的研究中,CD的平均年发病率为1.4/10万;在伊朗、亚洲和南非也观察到了类似的结果。

- 在一项亚太地区克罗恩病和结肠炎的流行病学研究(一项基于亚洲和澳洲八个国家的大规模人群研究)中,粗略的个人年总发病率为:

— 亚洲:炎症性肠病(IBD)为1.37/10万,溃疡性结肠炎(UC)为0.76/10万,克罗恩病(CD)为0.54/10万,未确定型IBD为0.07/10万。

— 澳洲:IBD为23.67/10万,UC为7.33/10万,CD为14.00/10万,未确定型IBD为2.33/10万。

— 中国是亚洲IBD发病率最高的国家,为3.44/10万。

— UC和CD的比率在亚洲为2.0,在澳洲为0.5[48]。

IBD在发达国家和发展中国家都是结核的一种重要的鉴别诊断。在潜伏感染率高的结核流行的发展中国家,对本身健康的个体进行“暴露”检测是不合适的。

3.3.4 其他需要考虑的鉴别诊断

- 腹膜假性黏液瘤

- 腹膜淋巴瘤

- 弥漫性腹膜平滑肌瘤

- 良性脾组织植入

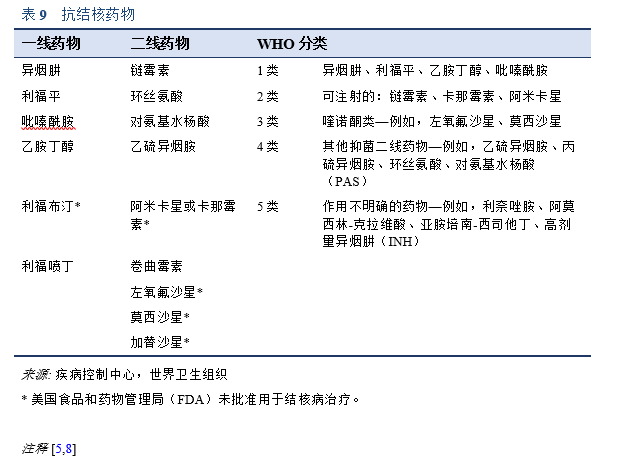

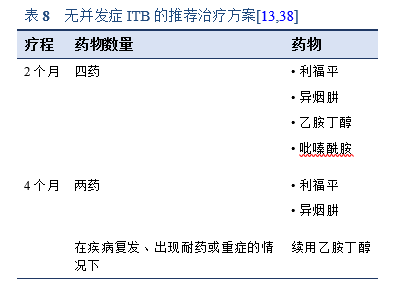

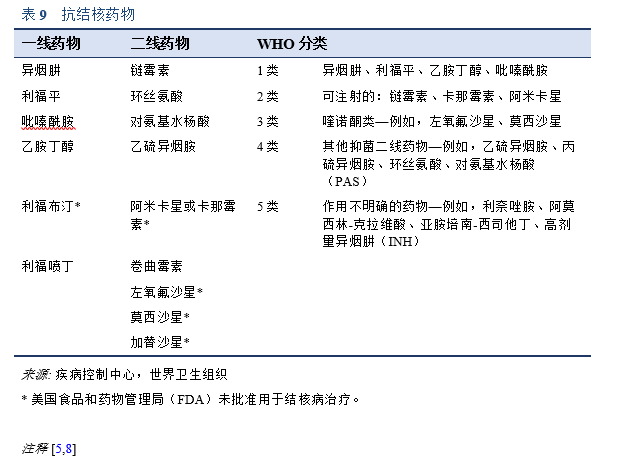

4.1 肺外结核的药物治疗

腹部结核患者应接受完整疗程的抗结核治疗。

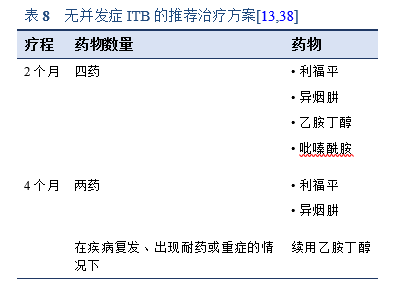

对于无并发症的ITB,目前推荐使用表8中详述的2个月疗程。应避免更长时间的治疗,因为它与依从性差和潜在有毒药物副作用风险增加有关。

• 肺外结核病应使用和肺结核病相同的抗结核药物方案进行治疗。6个月、9个月、和18-24个月的疗程均对肺外结核有效。

• Cochrane的一篇综述发现,没有证据表明6个月的治疗方案不足以治疗肠道和腹膜结核患者,但目前研究数量很少[5]。

• 抗结核治疗应该立即开始(在 HIV合并结核感染的情况下不需要考虑CD4计数如何)。

• 至少9个月的标准治疗对大多数及时开始合适治疗并依从的AIDS患者也是有效的。

• 要牢记并考虑到多重耐药的可能性。

• AIDS患者的结核病治疗与未感染HIV者的相同,但多重耐药结核在AIDS患者中更为常见。

4.2 副作用

异烟肼(INH)、利福平(RIF)或吡嗪酰胺(PZA)可能引起肝毒性

- 药物性肝炎可无症状或有症状[15]。

- 在无症状患者中,其定义为血清谷草转氨酶(AST)水平升高为正常上限的5倍以上。

- 在有症状患者中(常表现为腹痛、恶心、呕吐),其定义为AST水平升高为正常上限的3倍。

- 如果患者因AST显著升高至急诊就诊,应停止用药。

监测药物性肝毒性(DIH)或药物性肝损伤(DILI)[11]

- 接受一线抗结核药物治疗的患者应进行肝酶(转氨酶、胆红素和碱性磷酸酶)的基线测量。

- 有流行病学危险因素的患者应通过检测乙型和丙型肝炎排除急性病毒性肝炎。

- 建议在以下情况下重新测量肝酶—前3个月每2周一次,然后每月一次(对于基线正常的患者不需要):

— 基线结果不正常

— 疑似DIH反应

— 肝病(例如,乙型或丙型肝炎、酗酒)

— 怀孕或产后前3个月

— 序贯治疗期联合使用吡嗪酰胺

- 肝毒性症状包括:厌食、恶心、呕吐、尿色加深、黄疸、皮疹、瘙痒、乏力、发热、腹部不适(尤其是右上腹不适)、易产生瘀斑或出血以及关节痛。

— 必须对患者进行相关症状的教育。

— 每月随访时应直接询问患者这些症状。

— 当在每月随访间期出现任何体征或症状时,患者应立即报告。

- DIH的阳性预测因素:

— 年龄> 35岁(患结核病DILI的风险增加4倍)

— 女性

— 乙型肝炎(与非携带者相比,HBsAg携带者的风险增加4倍)

— 丙型肝炎(风险增加5倍)

— 饮酒

— 肝硬化

— 营养状况:中臂围< 20cm,基线低白蛋白血症

— 基因多态性(未在发展中国家用于检测肝毒性风险)

其他药物副作用包括胃肠道症状、皮疹和药物间相互作用。

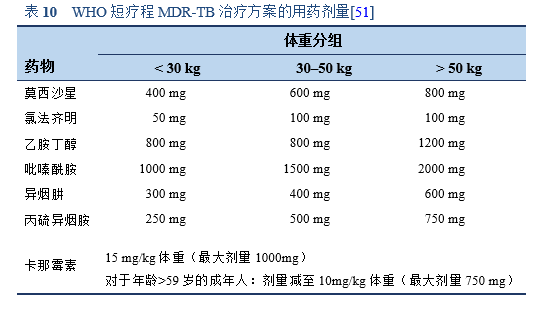

4.3 抗菌耐药性

从新诊断肺结核患者中分离出的MTB株中有2.4-13.2%出现了多重耐药(MDR),而在以前治疗过的患者中有17.4–25.5% 出现了多重耐药。广泛耐药性(XDR)几乎只见于既往接受过治疗的患者,约占MDR-TB的6%。

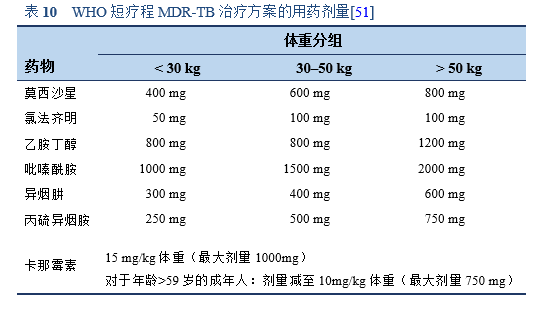

WHO短疗程MDR-TB治疗方案:

- 卡那霉素(一种可注射药物)、莫西沙星、丙硫异烟胺、氯法齐明、异烟肼、吡嗪酰胺和乙胺丁醇,在初始阶段联合用药4个月(如果患者在第4个月末痰涂片仍呈阳性,可选择延长至6个月)。

- 随后采用4种药物(莫西沙星、氯法齐明、吡嗪酰胺和乙胺丁醇)进行为期5个月的强化治疗。

- 每天服药1次,一周七天均需服药。

- 如果强化治疗期延迟,四个月后注射药物每周仅使用3次。

4.4 经验性治疗

在腹部结核病高发国家,如果临床特征相符—例如,临床、影像学和内镜结果均一致诊断腹部结核,并且可以充分排除其他常见疾病例如癌症、非特异性炎症性肠病、和其他特异性感染,可考虑使用2-3个月的经验性抗结核药物治疗[13]。

如果患者对治疗有反应,并且在随访结束后没有复发,则高度考虑结核性肠炎的诊断[8]。

需每周监测治疗反应,持续4-6周:

- 症状缓解

- 体重增加

- 在确定结核病治疗的反应上,血红蛋白水平的升高和C反应蛋白(CRP)水平的下降比血沉(ESR)的下降更敏感[52]。

然而,出于以下原因,建议在开始治疗前应先确定结核病诊断[11,17]:

- 克罗恩病患者对抗结核治疗的部分反应和MDR结核的出现降低了将ATT反应作为诊断结核病的有效性。

- 抗结核治疗可能有严重的副作用和致病率。

- 使用免疫抑制剂治疗的克罗恩病患者有更高的获得性感染的风险,包括结核感染—这可能导致两种疾病共存。

当腹腔镜无法使用或患者负担不起,以及患者不能手术时,腹水ADA检测对于快速诊断腹膜结核和开始经验性抗结核药物治疗至关重要。

对于高度怀疑腹膜结核并且ADA>30IU的患者, 可开始抗结核治疗。

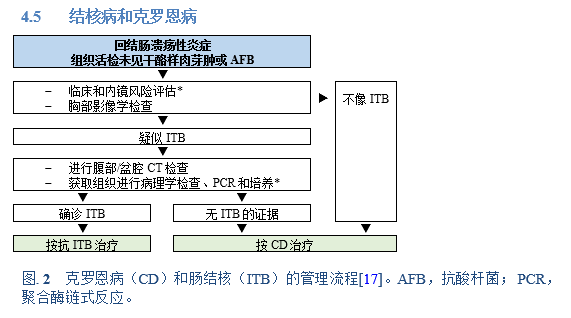

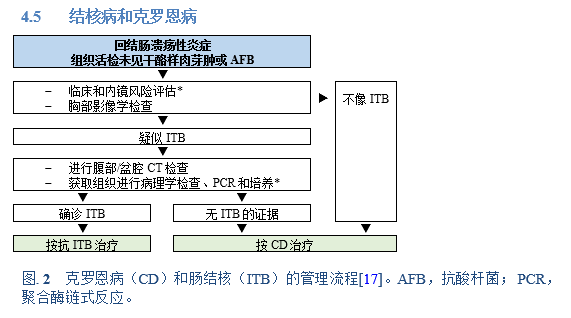

4.5 结核病和克罗恩病

注释:

• 如果不能进行PCR检测,考虑经验性抗结核治疗。

• 如果培养阳性,继续治疗,如果培养阴性则考虑克罗恩病。

* 临床风险评估包括源于结核高流行地区的既往结核病史和无腹腔脓肿的波动性高热。

ADA,腺苷脱氨酶;CT,计算机断层扫描;ITB,肠结核;PCR,聚合酶链式反应。

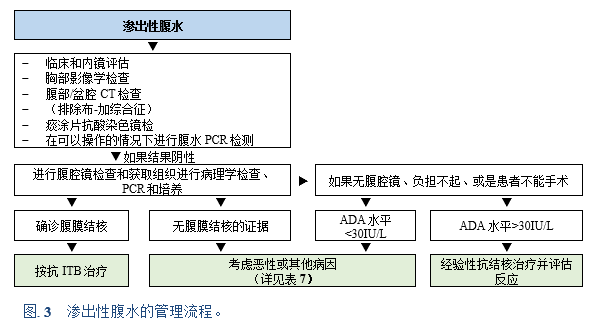

注释:

• 如果PCR不能进行且活检中没有腹膜结核的证据,可考虑经验性抗结核治疗并等待培养结果。

• 如果培养阳性,继续治疗;如果培养阴性,需考虑克罗恩病(虽然腹水在克罗恩病或其他原因中不常见)。

• 腺苷脱氨酶(ADA)活性在结核病、肝病和某些恶性肿瘤(以及其他疾病)中升高。

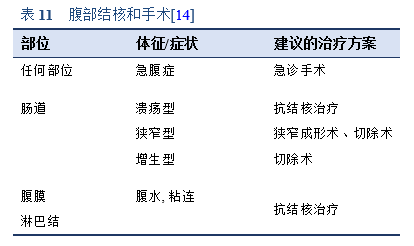

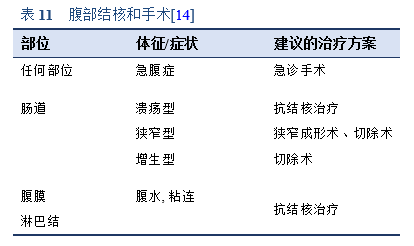

4.6 手术治疗

手术干预用于治疗并发症—纤维化、狭窄和急腹症—或诊断不明确时。

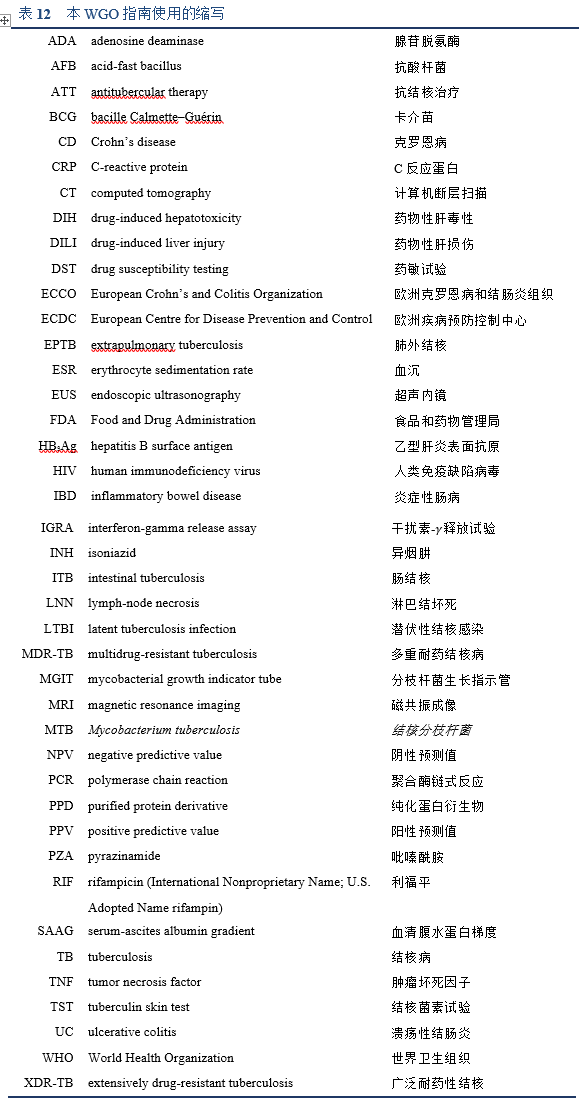

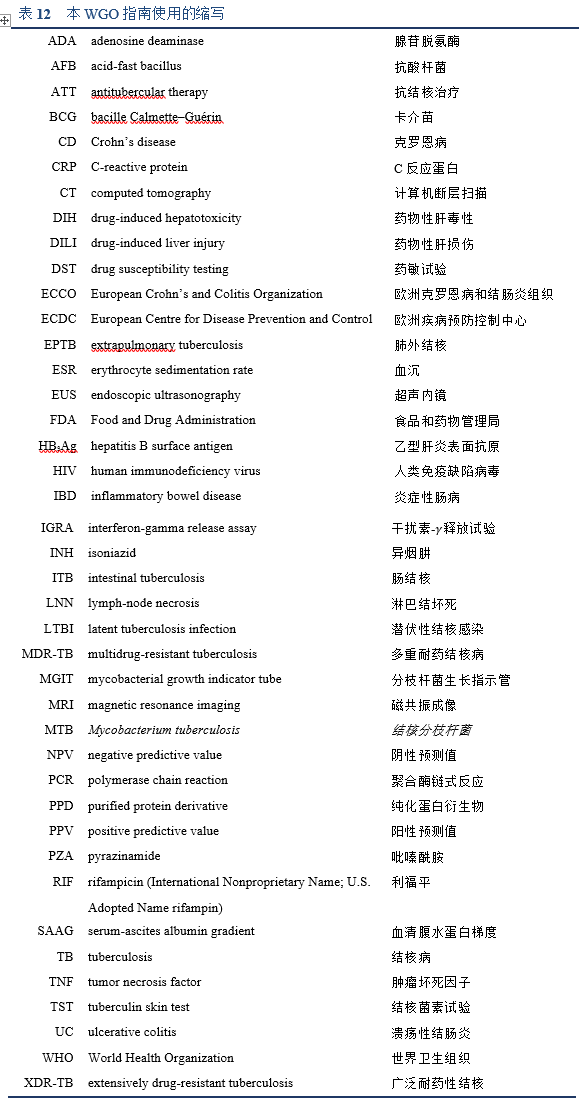

5.1 缩写

5.2 结核病和胃肠道疾病指南

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Use of interferon-gamma release assays in support of TB diagnosis. Stockholm: ECDC; 2011. doi: 10.2900/38588. 可从以下链接获取: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/1103_GUI_IGRA.pdf [42].

- [Diagnostic guideline of intestinal tuberculosis]. [In Korean.] Kim YS, Kim Y-H, Lee K-M, Kim JS, Park YS, IBD Study Group of the Korean Association of the Study of Intestinal Diseases. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53(3):177–86 [53].

- The diagnostic work-up in patients with ascites: current guidelines and future prospects. Oey RC, van Buuren HR, de Man RA. Neth J Med. 2016;74(8):330–5 [23].

- Index-TB guidelines: guidelines on extrapulmonary tuberculosis for India. Sharma SK, Ryan H, Khaparde S, Sachdeva KS, Singh AD, Mohan A, et al. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145(4):448–63. 可从以下链接获取: https://www.ijmr.org.in/article.asp?issn=0971-5916;year=2017;volume=145;issue=4;spage=448;epage=463;aulast=Sharma;type=2 [54].

- Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, Armuzzi A, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(6):443–68. 可从以下链接获取: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/8/6/443/421810 [9].

5.3 参考文献

1. World Health Organization. Tuberculosis: key facts [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2021 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

2. Raviglione MC. Tuberculosis. In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018. p. 1236–58.

3. Epstein D, Mistry K, Whitelaw A, Watermeyer G, Pettengell KE. The effect of physiological concentrations of bile acids on in vitro growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. S Afr Med J. 2012;102(6):522–4.

4. Pattanayak S, Behuria S. Is abdominal tuberculosis a surgical problem? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97(6):414–9.

5. Jullien S, Jain S, Ryan H, Ahuja V. Six-month therapy for abdominal tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD012163.

6. Noomene R, Ouakaa A, Jouini R, Maamer AB, Cherif A. What remains to surgeons in the management of abdominal tuberculosis? A 10 years experience in an endemic area. Indian J Tuberc. 2017;64(3):167–72.

7. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2018 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274453

8. Marshall JB. Tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(7):989–99.

9. Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, Armuzzi A, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(6):443–68.

10. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis — a challenging diagnosis [video] [Internet]. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2013 [cited 2018 Sep 24]. Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/extrapulmonary-tuberculosis-challenging-diagnosis

11. Sood A, Midha V, Singh A. Differential diagnosis of Crohn’s disease versus ileal tuberculosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(11):418.

12. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2017 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 [cited 2018 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

13. Abbas Z. Abdominal tuberculosis. In: Hasan M, Akbar MF, Al-Mahtab M, editors. Textbook of Hepato-Gastroenterology. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub; 2015. p. 68–76.

14. Kapoor VK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74(874):459–67.

15. Wang E, Sohoni A. Tuberculosis: a primer for the emergency physician. Emerg Med Rep [Internet]. 2006 Dec 24 [cited 2018 Jul 28]; Available from: https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/100438-tuberculosis-a-primer-for-the-emergency-physician

16. Khan R, Abid S, Jafri W, Abbas Z, Hameed K, Ahmad Z. Diagnostic dilemma of abdominal tuberculosis in non-HIV patients: an ongoing challenge for physicians. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(39):6371–5.

17. Almadi MA, Ghosh S, Aljebreen AM. Differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease: a diagnostic challenge. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(4):1003.

18. Rathi P, Gambhire P. Abdominal tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2016;64(2):38–47.

19. Kroot EJA, Hazes JMW, Colin EM, Dolhain RJEM. Poncet’s disease: reactive arthritis accompanying tuberculosis. Two case reports and a review of the literature. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2007;46(3):484–9.

20. Umapathy KC, Begum R, Ravichandran G, Rahman F, Paramasivan CN, Ramanathan VD. Comprehensive findings on clinical, bacteriological, histopathological and therapeutic aspects of cutaneous tuberculosis. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(10):1521–8.

21. Kurup SK, Chan CC. Mycobacterium-related ocular inflammatory disease: diagnosis and management. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006 Mar;35(3):203–9.

22. Figueira L, Fonseca S, Ladeira I, Duarte R. Ocular tuberculosis: position paper on diagnosis and treatment management. Rev Port Pneumol. 2017;23(1):31–8.

23. Oey RC, van Buuren HR, de Man RA. The diagnostic work-up in patients with ascites: current guidelines and future prospects. Neth J Med. 2016;74(8):330–5.

24. Sharma V, Singh H, Mandavdhare HS. Tubercular abdominal cocoon: systematic review of an uncommon form of tuberculosis. Surg Infect. 2017;18(6):736–41.

25. Puri AS, Sachdeva S, Mittal VV, Gupta N, Banka A, Sakhuja P, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis, management and outcome of gastroduodenal tuberculosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2012;31(3):125–9.

26. Moka P, Ahuja V, Makharia G. Endoscopic features of gastrointestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. J Dig Endosc. 2017;8(1):1–11.

27. Vaid U, Kane GC. Tuberculous peritonitis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5(1).

28. Yönal O, Hamzaoğlu HO. What is the most accurate method for the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21(1):91–6.

29. Portillo-Gómez L, Morris SL, Panduro A. Rapid and efficient detection of extra-pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis by PCR analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(4):361–70.

30. Mao R, Liao W, He Y, Ouyang C, Zhu Z, Yu C, et al. Computed tomographic enterography adds value to colonoscopy in differentiating Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis: a potential diagnostic algorithm. Endoscopy. 2015;47(4):322–9.

31. Sharma V, Rana SS, Ahmed SU, Guleria S, Sharma R, Gupta R. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration from ascites and peritoneal nodules: A scoping review. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6(6):382–8.

32. Vafa H, Arvanitakis M, Matos C, Demetter P, Eisendrath P, Toussaint E, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis diagnosed by EUS: one disease, many faces. JOP J Pancreas. 2013;14(3):256–60.

33. Pulimood AB. Differentiation of Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis in India in 2010. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(4):433–43.

34. Ko JK, Lee HL, Kim JO, Song SY, Lee KN, Jun DW, et al. Visceral fat as a useful parameter in the differential diagnosis of Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis. Intest Res. 2014 Jan;12(1):42–7.

35. Kirsch R. Role of colonoscopic biopsy in distinguishing between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(8):840–4.

36. Pulimood AB, Peter S, Ramakrishna B, Chacko A, Jeyamani R, Jeyaseelan L, et al. Segmental colonoscopic biopsies in the differentiation of ileocolic tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(5):688–96.

37. Pulimood AB, Ramakrishna BS, Kurian G, Peter S, Patra S, Mathan VI, et al. Endoscopic mucosal biopsies are useful in distinguishing granulomatous colitis due to Crohn’s disease from tuberculosis. Gut. 1999;45(4):537–41.

38. Dawra S, Mandavdhare HS, Singh H, Sharma V. Abdominal tuberculosis: diagnosis and management in 2018. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2017;18(4):271–4.

39. Penz E, Boffa J, Roberts DJ, Fisher D, Cooper R, Ronksley PE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for extra-pulmonary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(3):278–84, i–iii.

40. Shahidi N, Fu Y-TN, Qian H, Bressler B. Performance of interferon-gamma release assays in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(11):2034–42.

41. Starshinova A, Zhuravlev V, Dovgaluk I, Panteleev A, Manina V, Zinchenko U, et al. A comparison of intradermal test with recombinant tuberculosis allergen (Diaskintest) with other immunologic tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Int J Mycobacteriology. 2018;7(1):32–9.

42. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Use of interferon-gamma release assays in support of TB diagnosis: ad hoc scientific panel opinion [Internet]. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2011. (ECDC guidance). Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/1103_GUI_IGRA.pdf

43. Jin T, Fei B, Zhang Y, He X. The diagnostic value of polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis to distinguish intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(1):3–10.

44. Riquelme A, Calvo M, Salech F, Valderrama S, Pattillo A, Arellano M, et al. Value of adenosine deaminase (ADA) in ascitic fluid for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis: a meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(8):705–10.

45. Shen Y, Wang T, Chen L, Yang T, Wan C, Hu Q, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of adenosine deaminase for tuberculous peritonitis: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9(4):601–7.

46. Tao L, Ning H-J, Nie H-M, Guo X-Y, Qin S-Y, Jiang H-X. Diagnostic value of adenosine deaminase in ascites for tuberculosis ascites: a meta-analysis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79(1):102–7.

47. Garcia-Tsao G. Ascites. In: Dooley JS, Lok AS, Garcia-Tsao G, Pinzani M, editors. Sherlock’s diseases of the liver and biliary system. 13th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2018. p. 127–50.

48. Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia–Pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):158-165.e2.

49. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(12):720–7.

50. He Y, Zhu Z, Chen Y, Chen F, Wang Y, Ouyang C, et al. Development and validation of a novel diagnostic nomogram to differentiate between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease: a 6-year prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):490–9.

51. World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2021 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2019/consolidated-guidelines-drug-resistant-TB-treatment/en/

52. Lawn SD, Obeng J, Acheampong JW, Griffin GE. Resolution of the acute-phase response in West African patients receiving treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(4):340–4.

53. Kim YS, Kim Y-H, Lee K-M, Kim JS, Park YS, IBD Study Group of the Korean Association of the Study of Intestinal Diseases. [Diagnostic guideline of intestinal tuberculosis]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53(3):177–86.

54. Sharma SK, Ryan H, Khaparde S, Sachdeva KS, Singh AD, Mohan A, et al. Index-TB guidelines: guidelines on extrapulmonary tuberculosis for India. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145(4):448–63.